Ancient History: Guardians of the Fall Line

Deep Time: Ice Age to Contact

Ice Age & Early Peoples (15,000-12,000 years ago)

The earliest evidence of human presence in Virginia comes from sites like Cactus Hill, located just 45 miles southeast of the Rappahannock fall line. This site has yielded both Clovis and pre-Clovis artifacts, suggesting continuous human occupation for over 15,000 years.

Cactus Hill Significance: This National Historic Landmark provides crucial evidence that Virginia was a corridor for early human migration and settlement. The pre-Clovis artifacts challenge traditional models of when humans first arrived in North America, pushing back the timeline by several thousand years.

Archaic Period (10,000-3,000 years ago)

As the climate warmed and megafauna disappeared, Archaic peoples developed sophisticated hunting and gathering adaptations. This period saw the emergence of groundstone tools, fish weirs, and the earliest evidence of settled seasonal camps along major rivers. The Rappahannock fall line became increasingly important as a predictable resource zone where fish migrations, nut harvests, and game animals could be reliably accessed.

Evidence suggests the earliest petroglyphs may date to this period, when shamanic traditions and astronomical knowledge began encoding in stone. The serpent motifs at Snake Rock likely originated during this time when river spirits became central to regional spiritual practices.

Archaeological Evidence: In addition to petroglyphs, the archaeological record around Ficklen Island and the Fall Line yields other traces. Over the years, artifact collectors have found stone projectile points (arrowheads and spearheads) on the terraces above the falls, some dating back to the Archaic period (c. 3000-1000 BCE). These indicate long-term utilization of the locale, at least seasonally.

Woodland Period (3,000-400 years ago)

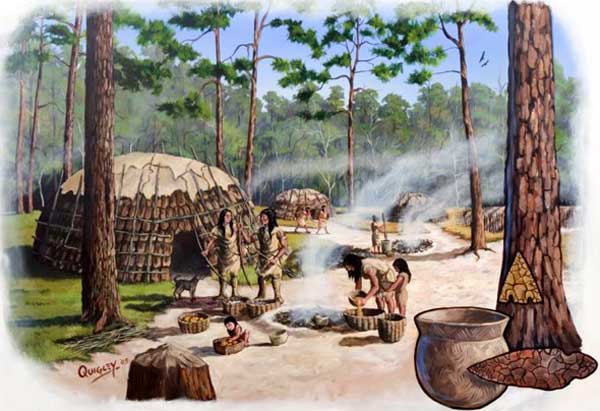

The Woodland Period marked revolutionary changes: the introduction of pottery, bow and arrow technology, and increasingly sophisticated fishing techniques. Large permanent villages appeared along major rivers, and the fall line became a crucial boundary between emerging cultural groups. This period saw the construction of elaborate fish weirs and the full development of the astronomical-ceremonial complex.

The three sisters agriculture (corn, beans, squash) supplemented traditional hunting and gathering, supporting larger populations and more complex social organization. The fall line's ceremonial importance reached its peak during this period.

Intensive Use Evidence: Pottery sherds from the Late Woodland period (c. 1000-1600 CE) have been found as well, suggesting more intensive use in the centuries just before European contact – likely corresponding to the village communities John Smith noted. No formal excavation has yet uncovered a fire pit or posthole pattern (which would signify a permanent village), but shallow test pits have revealed charcoal flecks and burnt river cobbles in certain spots, consistent with hearths or earth ovens used during short-term camps.

Contact Era (1600s)

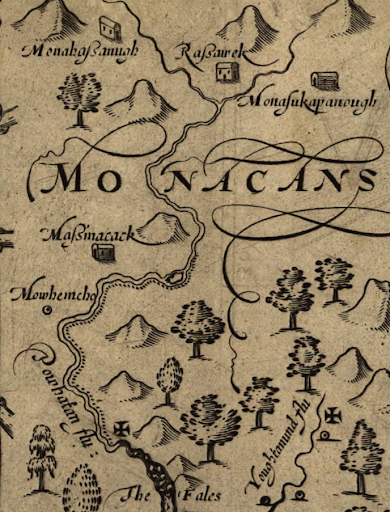

At European contact, the fall line marked the boundary between Algonquian-speaking Powhatan allies to the east and Siouan-speaking Manahoac to the west. This cultural frontier was also sacred neutral ground where both groups maintained ceremonial sites and conducted essential trade. John Smith's 1608 encounter at the falls marked the beginning of a new era that would forever change the ancient landscape.

Despite political differences, the fall line functioned as neutral territory under special protocols that recognized its spiritual importance to all peoples.

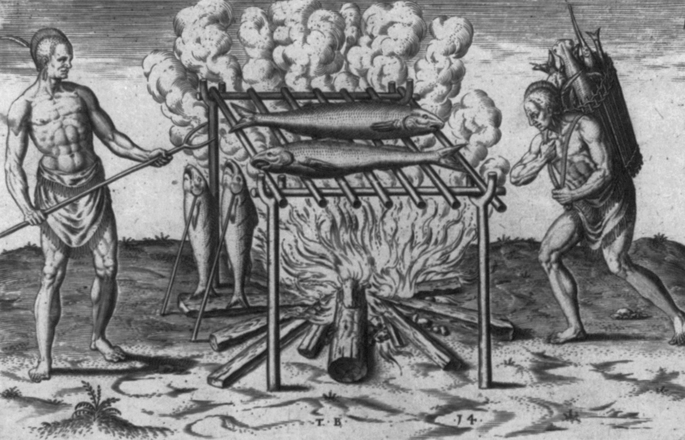

Stone Fish Weirs: So far, the most compelling physical evidence for communal food processing are the stone fish weirs recorded in the river. Downstream of the current fall line park, aerial surveys have spotted alignments of stones in V-shaped patterns in the water – almost certainly the remnants of indigenous fishing weirs built to guide fish into traps.

One such stone weir is known at the former Embrey Dam site. These weirs attest to the systematic, possibly ritualized harvesting of fish. In some Algonquian traditions, the first catch from a weir each season had to be taken with certain rituals (prayers, perhaps sprinkling tobacco on the water) to ensure the spirits of the river continued to send fish. The fact that we have petroglyphs and weirs in close proximity at Fredericksburg underscores the idea of an integrated cultural landscape: one where the spiritual is literally etched into the rock, and the sustenance strategy is built into the river.

Historical Documentation: Combined with John Smith's account of a large temporary "hunting town" in 1608, the evidence points to the falls being used primarily as a seasonal camp where structures were temporary (wigwams easily leaving little trace) and the same spots reused periodically. The presence of communal roasting pits or emplacements for drying racks (to smoke fish) would be expected; while not documented, these could be inferred by concentrations of charcoal and fish bones if looked for.

Cultural Convergence

Algonquian Peoples (East)

Rappahannock, Patawomeck, Pamunkey

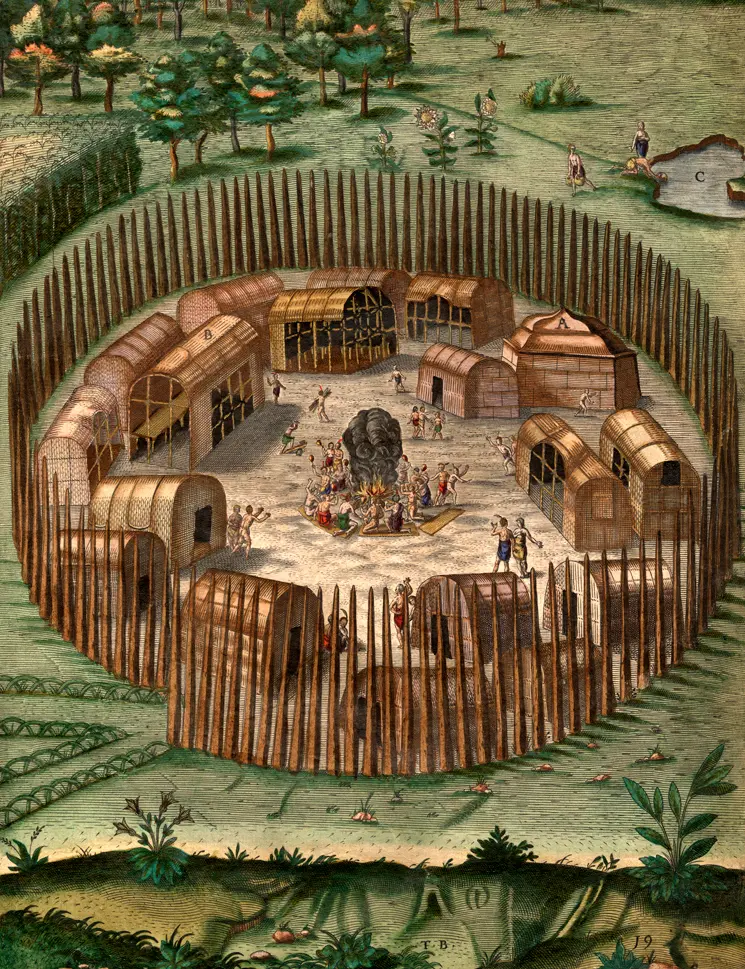

Part of Wahunsenacawh's (Powhatan's) confederation, these groups controlled lands downstream from the falls. They brought maritime and tidewater traditions to the ceremonial gatherings, including sophisticated fishing techniques, canoe technology, and knowledge of Chesaperay resources. Their villages featured palisaded settlements and extensive agricultural fields.

Siouan Peoples (West)

Manahoac Confederation

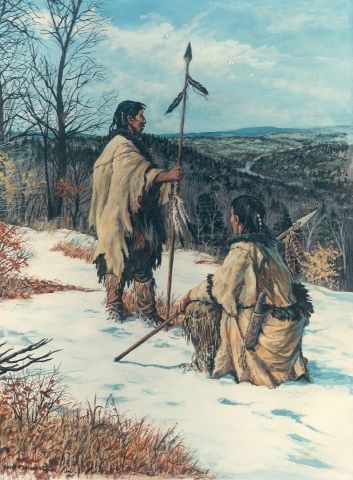

Controlled territory upstream from the falls, these semi-nomadic hunter-gatherers brought Piedmont and mountain wisdom to the sacred landscape. They were expert in stone tool technology, upland hunting techniques, and possessed deep knowledge of interior forest resources. Their seasonal camps followed ancient trails through the Virginia Piedmont.

Sacred Neutral Ground

The Fall Line

Despite political differences, the fall line functioned as neutral territory where ancient protocols recognized its spiritual importance to all peoples. The thundering rapids, serpent petroglyphs, and astronomical alignments created a shared sacred geography that transcended tribal boundaries. Here, different groups gathered for ceremonies, trade, and the maintenance of cosmic balance.

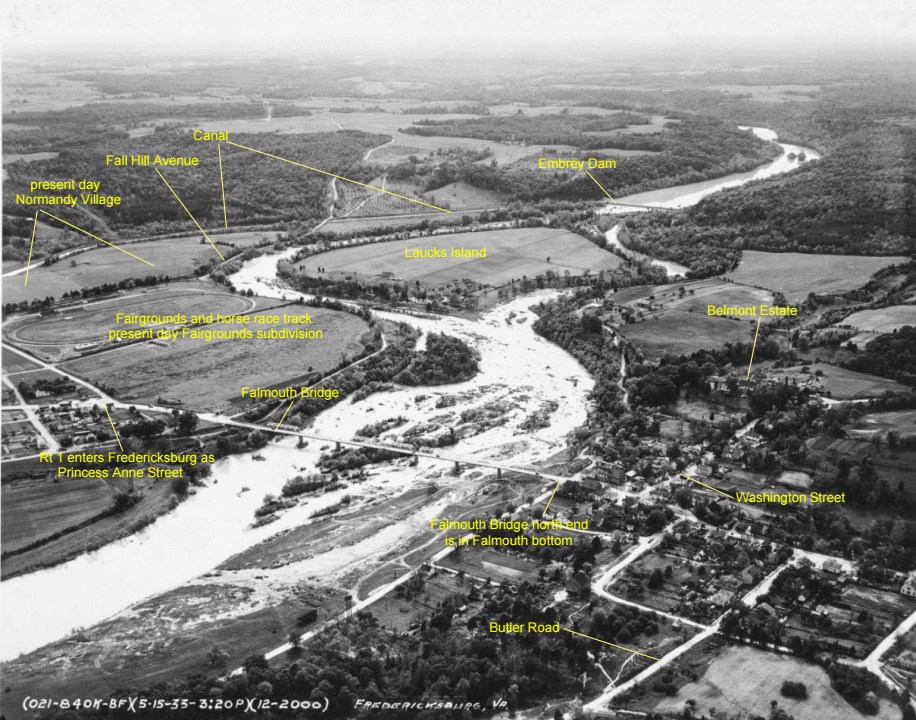

THE ENIGMA OF LAUCK'S ISLAND

Sacred Island Landscape

The natural beauty and strategic location that made Lauck's Island a focal point of human activity for millennia

Historical Perspective

Later historical use of the island, showing the continuing human connection to this strategic location

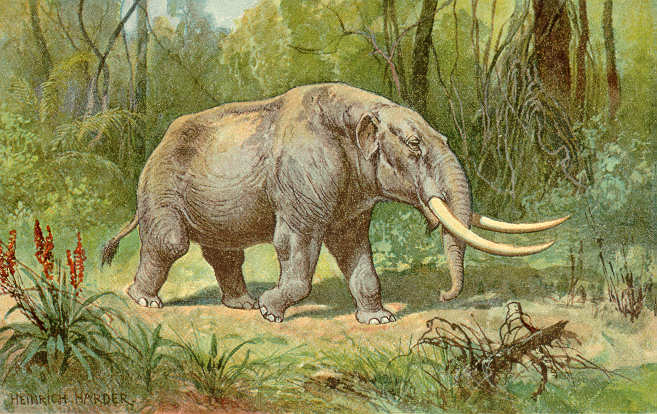

Mastodon Mystery

Mastodons roamed Virginia until approximately 10,000 years ago, overlapping with early human presence

Also known historically as Hunter's Island, Lauck's Island holds secrets from Virginia's deepest past. This strategic location within the fall line complex likely witnessed some of the earliest human-environment interactions in North America. Industrial operations during the 18th and 19th centuries—including ironworks and milling operations—may have disturbed crucial archaeological evidence dating back to the Ice Age.

The island was abandoned after a devastating flood in 1937, but its archaeological potential remains largely unexplored. Modern investigations using ground-penetrating radar and careful stratigraphic excavation could reveal evidence of the earliest human-environment interactions at the fall line, possibly including rare evidence of late Pleistocene hunting camps and the transition from big-game hunting to the sophisticated resource management systems of later periods.

Recent research at sites like Cactus Hill has revolutionized our understanding of when humans first arrived in Virginia. Lauck's Island, with its strategic position and long history of human occupation, may hold similar secrets about the earliest chapters of North American prehistory. The intersection of ancient rapids, predictable animal migration routes, and abundant stone tool materials made this location a natural focus of human activity for millennia.

Local lore speaks of "giant bones" discovered during 19th-century construction projects, hinting at the tantalizing possibility that early peoples witnessed and hunted the last Ice Age megafauna. Mastodon remains have been found throughout Virginia, with several sites documenting human-mastodon interactions. The island's position at the fall line would have made it an ideal hunting ground where large mammals came to drink and where ancient hunters could predict their movements.

The island's complex stratigraphy likely preserves a continuous record of human occupation spanning thousands of years. From Paleo-Indian hunters tracking mastodons to Archaic peoples developing the first fish weirs, to Woodland communities establishing the ceremonial complex, each era left its mark on this sacred landscape.