The Religion of the Natives

Three Worlds Sacred Cosmology

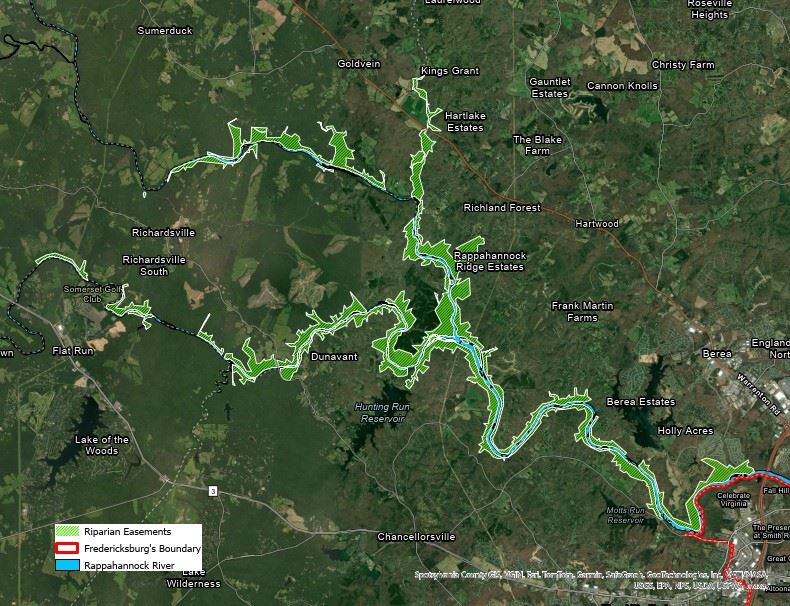

Indigenous Eastern Woodlands peoples understood the universe as three interconnected realms, each populated by distinct spiritual beings and accessible through specific locations and rituals. The Rappahannock fall line naturally embodied this sacred geography.

🌅 The Upper World

Domain: Sky, Sun, Moon, Stars, Thunder Beings

At the Falls: The Overlook connected ceremonies to celestial forces. Elevated fire ceremonies, astronomical observations, and communication with Sky Spirits occurred here. Eagles soaring above the rapids served as messengers between worlds, carrying prayers to the Creator and bringing wisdom back to earth.

Spiritual Beings: Thunderbirds, solar deities, star spirits, and ancestor spirits who completed their earthly journey

🌍 This World (Middle Realm)

Domain: Human life, animals, plants, daily activities

At the Falls: Islands and shores where humans safely dwelled while accessing both spiritual realms. The Indian Punch Bowl served as the community hearth where families gathered, tools were made, and stories were shared. This realm maintained the delicate balance between Upper and Lower worlds.

Spiritual Beings: Animal spirits, plant teachers, ancestor spirits who guide the living, and spirits of place

🐍 The Lower World

Domain: Water spirits, Horned Serpents, underground forces

At the Falls: Snake Rock and the Recess Pool served as gateways to underwater realms. The Great Serpent controlled river flow and fish abundance, emerging during droughts to signal when special ceremonies were needed. The swirling pools and underwater caverns were understood as passages to the spirit world.

The Great Horned Serpent

Algonquian oral traditions speak of a great Horned Serpent dwelling in rivers and lakes, associated with rain, thunder, and life-giving water. Its coiling shape represents water's flow, while its power brings both renewal and destruction.

Spiritual Beings: The Great Horned Serpent, water spirits, fish spirits, guardians of underground springs and caves

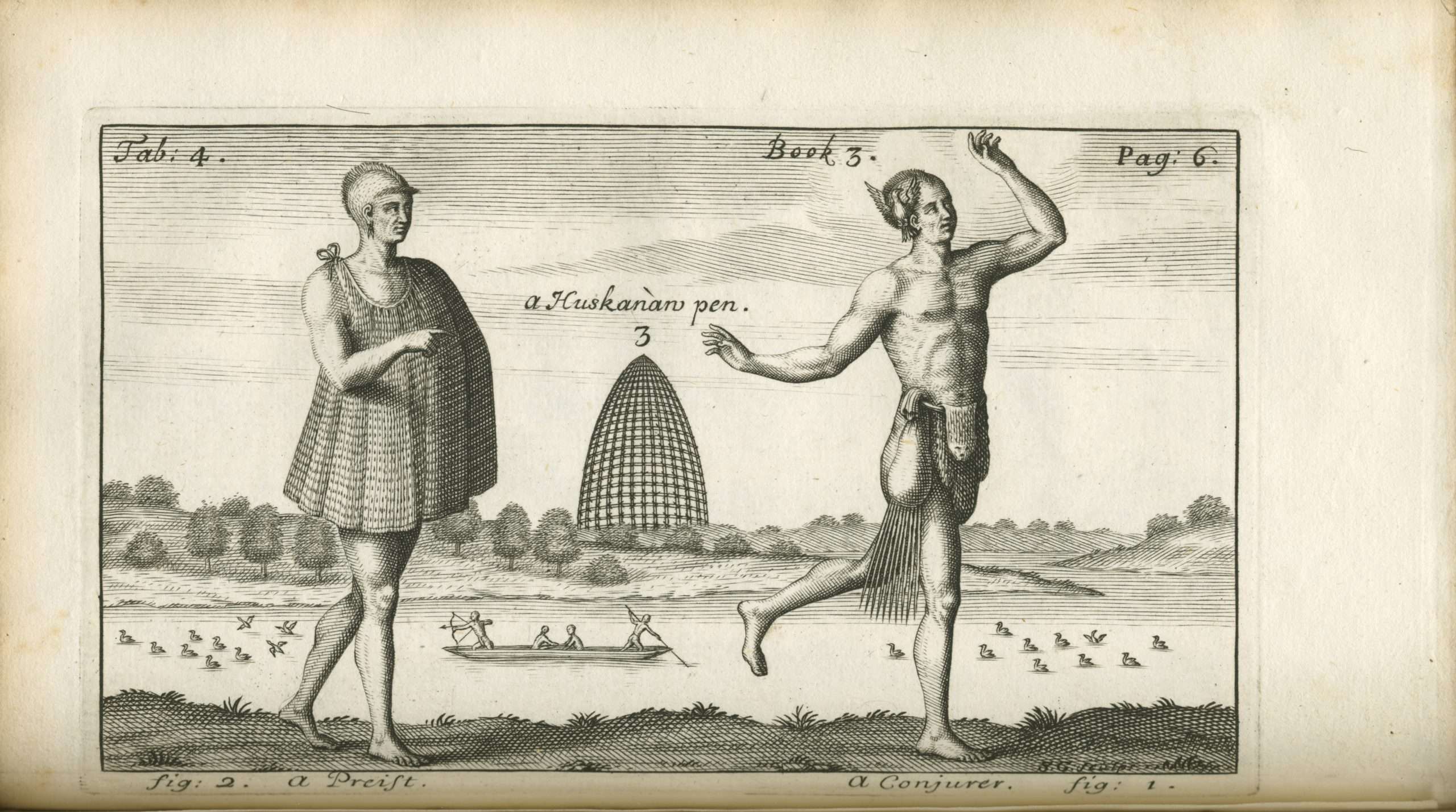

🌿 The HUSKANAW: Sacred Initiation Ritual

The Most Sacred Ceremony

The Huskanaw represented the most important spiritual transition in Powhatan society - the transformation of boys into men through a profound spiritual journey guided by plant teachers and ancestor spirits.

The Sacred Process: Young men were taken to isolated forest locations where they consumed wysoccan (Jimsonweed/Datura), a powerful plant medicine that induced visions and spiritual communication. During this controlled poisoning, initiates experienced death and rebirth, forgetting their childhood identity to emerge as spiritually awakened adults.

Connection to the Falls: The Rappahannock falls provided the perfect setting for Huskanaw ceremonies. The dramatic landscape of rushing water, echoing cliffs, and secluded pools created ideal conditions for vision quests and spiritual transformation. The Indian Punch Bowl may have been used to prepare the sacred wysoccan mixture, while Snake Rock served as a focal point for ceremonies honoring the serpent spirits that guided initiates through their spiritual journey.

Astronomical Significance

The Punch Bowl's placement on an open knoll suggests astronomical alignment significance. On equinoxes, midday sun might strike directly into the basin, creating a celestial timepiece for timing seasonal ceremonies including Huskanaw initiations.

Spiritual Transformation: The ceremony represented death of the child-self and rebirth as a spiritually mature adult. Initiates returned to their communities with new names, adult responsibilities, and direct connection to the spirit world. Those who didn't survive the ordeal were believed to have been called to join the ancestors in the Upper World.

Spiritual Significance: Transformation from child to adult, direct communication with spirits, preparation for adult responsibilities and spiritual duties

🐍 Symbolic Significance of the Snake

Sacred Duality

In Algonquian spirituality, snakes embodied profound duality - both destroyer and protector, bringer of death and renewal. Even the word "Iroquois" came from an Algonquian word for "snake," acknowledging spiritual power rather than insult.

Local Presence & Symbolism: The Rappahannock region hosted numerous snake species, including rattlesnakes in rocky outcrops. Tribes likely had snake clan or totem beliefs, with petroglyphs serving as territorial markers ("this area under Snake Clan protection") or spiritual warnings ("beware of the spirit here").

Spiral & Cyclical Symbolism: Spiral petroglyphs represented the cycle of life, sun's path, or spiritual portals. These symbols could indicate:

- Solar cycles: Stylized sun representing growth and health deities

- Water portals: Whirlpools as "spirit doors" between worlds

- Afterlife beliefs: Cyclical burial arrangements reflecting rebirth promises

The River as Living Serpent

The Rappahannock itself may have been personified as a great serpent - winding through the landscape, periodically swelling with rain then receding. Serpent carvings on drought-exposed rocks appeared when the river "breathed out" and disappeared when it "inhaled."

Mythological Context: Coastal Virginia Algonquian myths spoke of giant water beings including the "Piant" - a fabulous reptile living in water. Capricious spirits inhabited rock crevices, requiring travelers to offer tobacco or food when passing dangerous rapids or strange rocks.

Spiritual Teaching: Snakes (shedding skin = renewal), spirals (cycles), pools (cleansing), rocks (memory) reinforced harmony with nature's cycles

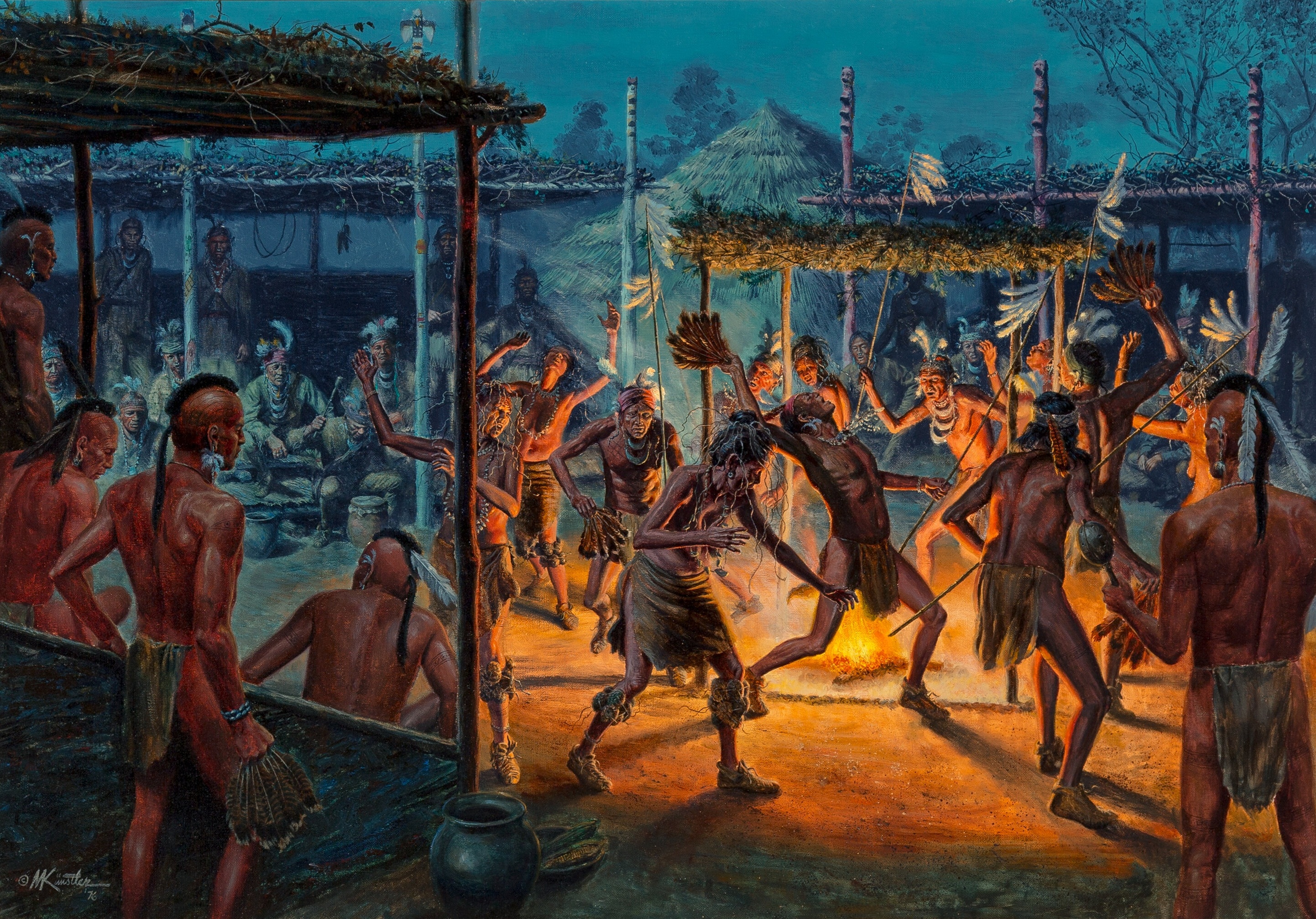

Sacred Practices & Ceremonies

🐟 First Fish Ceremonies

Each spring when shad and sturgeon ran upstream, the first catch received ceremonial treatment. Elder fishermen constructed elaborate stone fish weirs below the falls while communities prepared for days of celebration.

Sacred Process: Before setting weirs or casting nets, fishermen offered tobacco on Snake Rock to request permission from river spirits. The Indian Punch Bowl may have been used to prepare ritual foods - mixing fish oil with berries or creating ceremonial pastes shared with both community and spirits.

🌾 Harvest Festivals

Late summer gatherings celebrated the "three sisters" (corn, beans, squash) and forest abundance. The Indian Punch Bowl likely prepared sacred foods and ceremonial drinks for these communal celebrations.

Ceremonial Drinks: The bowl may have brewed herbal teas or tisanes for group rituals. Controlled doses of wysoccan (different from Huskanaw intensity) could be prepared for community purification ceremonies, or the "poison" mixing might refer to visionary potions rather than arrow treatments.

🔥 Vision Quests

The dramatic landscape provided ideal conditions for spiritual seeking. Young people and shamans used the Overlook's isolation and the Recess Pool's reflective surface for vision work and communication with spirits.

Spiritual Practice: Shamans could sit by the Recess Pool at night, using star reflections for divination, or position themselves under cliffs during thunderstorms to receive messages from Thunder Beings - the adversaries of water serpents in Algonquian lore.

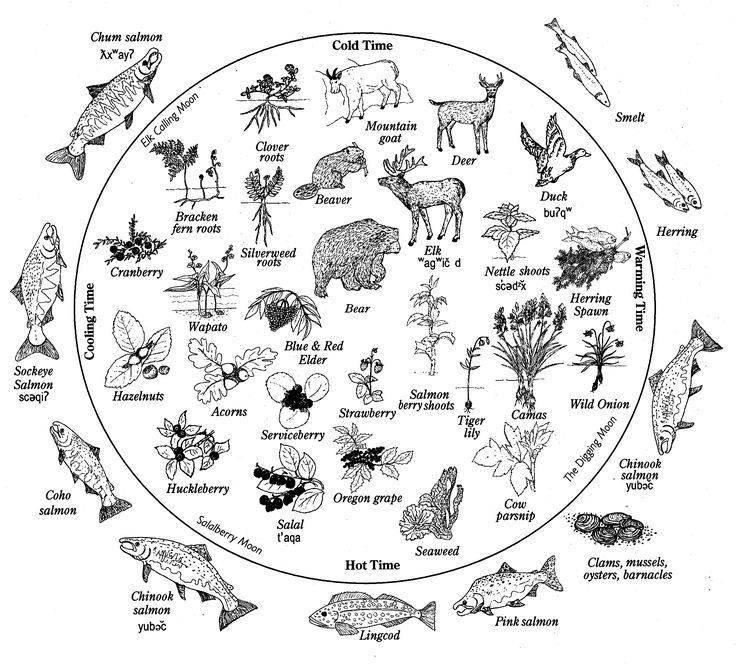

🌟 Astronomical Ceremonies

Solstice and equinox observations from the Overlook aligned human activities with cosmic cycles. The rising and setting sun marked times for planting, harvesting, and spiritual transitions.

Celestial Calendar: Complex calculations tracked lunar months, eclipse cycles, and planetary movements, creating sophisticated calendars that guided all aspects of life from agriculture to ceremony timing.

The Contact Era Ceremonial Complex (1600s)

John Smith's Observations (1608)

Smith found evidence of large Native encampments at the falls, including the "hunting town" Mahaskahod that gathered "several hundred Indians from four or more distant villages" on the Rappahannock banks above the big island.

Neutral Territory: The falls constituted shared resource zones used by multiple Rappahannock-speaking communities seasonally. The concentration of petroglyphs and modified rocks in a small area implies communal ceremonial purposes rather than single-village use.

Intertribal Ceremonies: Multi-day festivals involved different clans camping on islands and banks, sharing food, stories, and rites honoring the river's gifts. These "hunting festivals" coincided with seasonal transitions and featured ceremonial drinking, dancing, and communal feasts.

Sacred Geography Integration: High points along the river contained ossuaries (communal bone burials) intentionally intervisible with village sites, creating integrated sacred landscapes where places of dead and living maintained spiritual connectivity.

The Sacred Cycle

These ceremonies formed an integrated spiritual calendar maintaining harmony between the three worlds. Each ritual reinforced others, creating webs of sacred practice sustaining both community and landscape. The fall line served as the axis around which this spiritual universe revolved.

Modern Understanding

Archaeological and ethnographic research continues revealing the sophistication of these spiritual systems. The precision of astronomical alignments, complexity of ecological knowledge, and depth of ceremonial traditions demonstrate that the Rappahannock fall line was one of ancient North America's great sacred centers.