Burial Mound (Sophia Street Park) – Resting Place of Many Spirits

Sacred Ground Revealed

In downtown Fredericksburg, near the banks of the Rappahannock at Sophia Street, lies a subtle rise of land that local tradition long referred to as an "Indian burial mound." This knoll, today part of Riverfront Park (around latitude 38.3011° N), was indeed an ancient high point overlooking the river bend, revealing a complex, multi-layered history of sacred use spanning millennia.

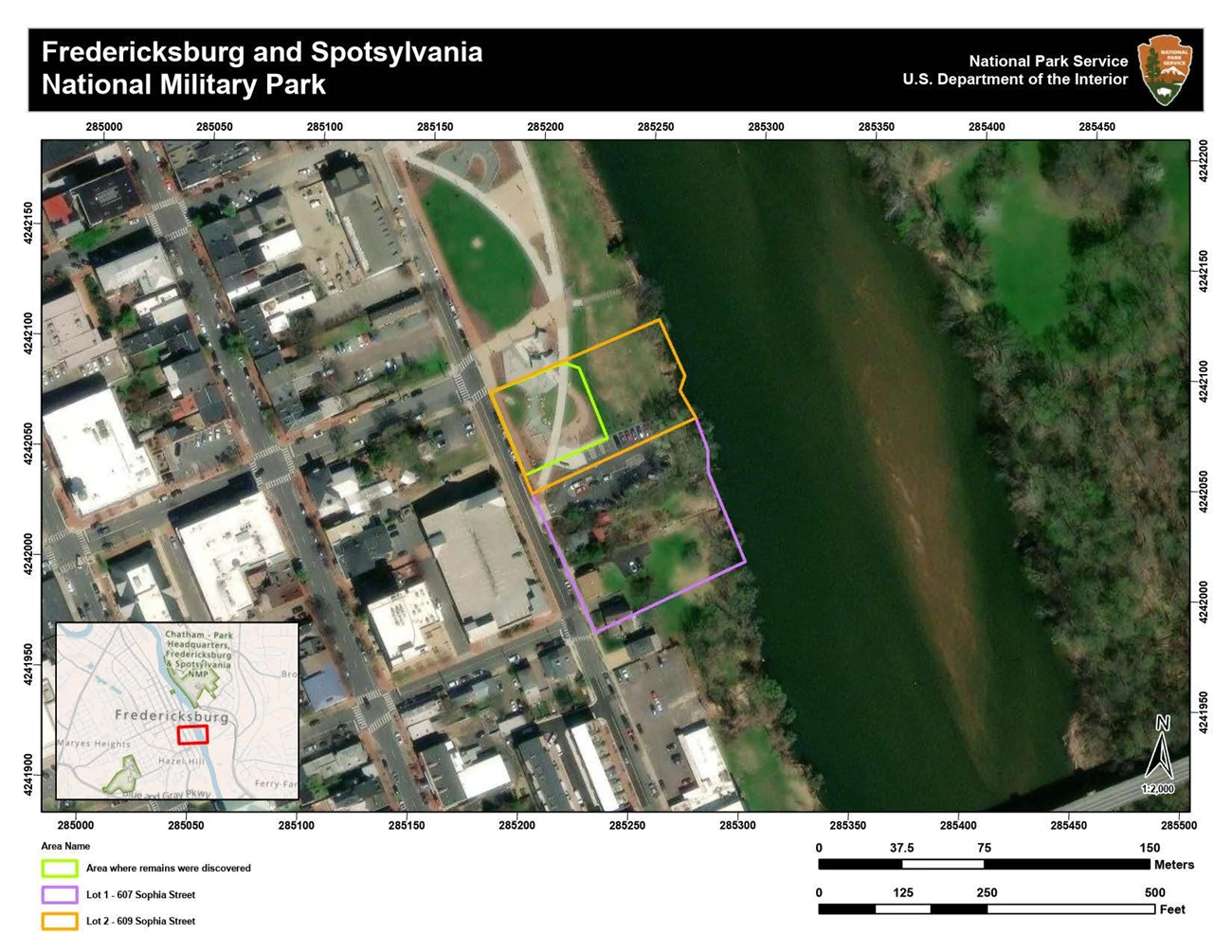

The 2015 Archaeological Discovery

In 2015, construction crews inadvertently sliced into the mound and uncovered human remains and thousands of artifacts, prompting an emergency excavation. The findings showed that the mound was geologically natural in origin (a Pleistocene sand/gravel deposit from an old river channel), but had been used and modified by humans for generations.

Artifacts Discovered: The archaeological investigation revealed significant Native American artifacts including Woodland period pottery sherds (dating 1000-1600 CE), stone projectile points from various periods, fire-cracked rocks indicating cooking hearths, and lithic debitage (stone tool-making debris). These findings demonstrate continuous indigenous use of the site for ceremonial and domestic purposes over millennia.

Prehistoric stone flakes, pottery sherds, and fire-cracked rocks were found within the mound's soil, indicating that Native Americans camped or worked at this spot repeatedly over thousands of years. Later, during the Civil War, the mound area (then part of a property with a house) was used as a burial ground for Union soldiers who died in a nearby field hospital. Even later, in the 1920s, the mound was partially leveled to build a lodge, adding another layer of fill.

Despite these disturbances, the fact remains: this little hill has been a magnet for human activity since time immemorial. The final archaeological report noted "the mound was a natural feature… used by generations of prehistoric and historic occupants," a gentle way of saying that it is a palimpsest of human stories.

Part of the Sacred River Corridor

The known burial mound at Sophia Street (Riverfront Park) is particularly interesting in pattern. Although ultimately it turned out to be a natural hill used in historic times as a mass burial for Civil War soldiers, its use by "prehistoric occupants" indicates it was a notable landmark even in Native times. Indigenous people likely used that mound (essentially a high river terrace remnant) perhaps as a village site or look-out.

Its location is only ~2 river miles below Ficklen Island. One could almost draw a line: from Haqqasod upstream of the falls, to the falls ceremonial sites, to the Sophia Street area (which might correspond to a documented 17th-century village site of the Rappahannocks or a sub-group). Such a line traces an ancient travel and trade corridor along the Rappahannock. It underscores that the falls were central, not peripheral, to the Indigenous cultural landscape – connecting communities upriver and down.

Virginia Burial Mound Context: This site fits the broader pattern of Native American burial practices throughout Virginia. Similar mounds have been documented along the James, York, and Potomac rivers, with the Great Indian Warpath connecting many of these sacred burial sites. The Monacan Indian Nation's ancestral burial grounds near present-day Lynchburg, and the Powhatan ossuary sites throughout the Tidewater region, demonstrate a sophisticated understanding of sacred geography where the dead were buried in locations that maintained spiritual connections to the living.

Why This Sacred Location?

Why would Native people favor this mound? Several reasons emerge. First, its strategic location: it is right by a natural ford of the river (near present-day Fredericksburg city docks), making it an ideal gathering place. Tribes traveling up and down river would stop at this ford; those crossing east-west (from the fall line to Potomac or to the Piedmont) also converged here.

The mound, being elevated, stayed dry in floods and offered a vantage to watch over the area. This made it a likely spot for a seasonal camp or meeting ground. The presence of diverse artifacts in the mound's soil supports that it wasn't one-time use, but recurrent – possibly as a fall harvest camp or a neutral council ground between different groups.

Notably, the 1608 John Smith accounts mention a skirmish with Manahoacs near the falls and then parley; could it be that after that encounter (which happened upriver), the peacemaking occurred near this very mound? It's speculative, but such prominent spots often became traditional council grounds known to multiple tribes.

Spiritual and Burial Aspects

Many Native cultures deliberately buried their dead on high ground near water. While no definitively pre-colonial burials were reported from the 2015 dig (most bones found were consistent with Civil War-era bodies), it remains possible that much older burials existed but were destroyed in prior centuries (earlier construction or river erosion).

The concept of an "Indian mound" in local lore may have originated from 19th-century residents finding arrowheads or bones and assuming a prehistoric burial. Even if not a formal mound built by natives, the hill could have held isolated burials or reburials (e.g., someone who died during a trip might be interred at a convenient high spot).

The Fredericksburg falls region was contested and saw warfare; slain warriors could have been laid to rest on this hill as a sign of honor, their graves overlooking the river they strove to defend. The Algonquians of Tidewater typically used ossuaries (mass reburial pits) in certain periods, but those were usually farther east. Piedmont tribes might have favored cairn burials on hills.

Virginia Burial Traditions: Archaeological evidence from similar sites throughout Virginia reveals sophisticated burial practices. The Monacans created elaborate stone cairns on hilltops, while Coastal Algonquian groups developed complex ossuary systems where bodies were periodically disinterred and reburied in communal graves. The presence of grave goods including pottery, copper ornaments, and shell beads demonstrates the spiritual importance of these burial sites in connecting the living with ancestral spirits.

Astronomical and Ceremonial Use

Astronomically, the Sophia Street mound's position in the river bend might relate to directional symbolism. It sits near where the river's course turns – downstream from the falls, the Rappahannock flows mostly eastward toward the Chesapeake. Thus, from the mound you look east along the river. This means on the eastern horizon, each day's sun rises roughly aligned with the river's trajectory.

A person standing on the mound at dawn would see the sun coming up "out of the river." For cultures that view rivers as the domain of an Earth/sun deity or as the path of life, that sight is rich in meaning. One can imagine an elder beginning the day with a prayer as the sun's reflection glittered on the water, maybe interpreting the interplay of light and water as an omen.

Additionally, the mound being elevated could have served as a calendrical marker with surrounding landscape: for instance, perhaps on summer solstice, the sunrise aligns with a notch on the distant tree line as seen from the mound. Or on winter solstice, the sun might rise aligned with a prominent point of the river bluff down east. Such alignments have been documented at various indigenous sites where natural features mark the sun's extremes.

A Platform for Sacred Fire

If we think of the mound as a "platform", it could host gatherings where fires were lit (a beacon visible up and down river). The concept of sacred fire on a mound is reminiscent of temple mounds in Mississippian culture further south and west; while Virginia Algonquians did not build platform mounds, they did maintain sacred fires for certain rituals (the Powhatans, for example, kept a perpetual fire in the temple of the priests).

Perhaps during intertribal councils at this neutral ground, a fire was kept atop the hill as a symbol of peace or as a signal. The panoramic view would let people see enemies or friends approaching by canoe. Interestingly, colonial accounts mention that the Rappahannock (tribe) did have a fortified town and also sent signals via smoke along the river – a place like this mound could have been a signaling station to communicate between inland groups and those toward the coast.

Sacred Fire Traditions: Archaeological evidence of fire-cracked rocks and charcoal deposits found at the site aligns with Native American sacred fire practices documented throughout the Eastern Woodlands. These ceremonial fires served multiple purposes: purification rituals, seasonal celebrations, ancestor veneration, and inter-tribal communication. The elevated position would have made any fire visible for miles along the river corridor, serving as a beacon for travelers and a spiritual focal point for ceremonies.

Modern Recognition and Future Research

The rediscovery of human remains in 2015, albeit from a later era, has renewed interest in the mound's history. City authorities now recognize the sensitivity of the site – it contains layers of Fredericksburg's heritage, indigenous and otherwise. For the Native American community, this underscores a truth: the Rappahannock River is lined with such places where the veil between past and present is thin. The spirits of those who lived and died here still linger.

Indeed, the Algonquian view of land held that "[the Indian] conceived its waterfalls and ridges… to be inhabited by myriads of spirits… he held daily communion [with them]. His homeland was holy ground, sanctified… as the natural shrine of his religion." This mound, as a ridge by a waterfall, fits that description of holy ground.

As a note for further exploration, ground-penetrating radar could be employed on undisturbed parts of the mound to check for burial pits or postholes (which might indicate a structure or palisade on the hilltop). Any such findings would deepen our understanding of how the space was organized.

Collaborative Research: Future archaeological investigations should involve tribal representatives from the Rappahannock Tribe, Monacan Indian Nation, and other Virginia tribes to ensure culturally appropriate research methods and interpretation. The site's potential for revealing pre-contact burial practices, artifact assemblages, and settlement patterns makes it crucial for understanding the broader sacred landscape of the Rappahannock River corridor.

Continuity of Sacred Use

While the Sophia Street "burial mound" may not be a built mound like those in the Ohio or Mississippi valleys, it is no less significant. It highlights how Indigenous sacred geography was often tied to natural landforms adapted for use. A hill becomes a burial place; a river bend becomes a meeting ground.

The continuity of its use into the Civil War (albeit for tragic reasons of war burials) ironically reinforces its character as a resting place for souls. Today, Riverfront Park incorporates the mound's story into the city's narrative, hopefully with input from tribes to properly honor the First Peoples who found it first.

Even without definitive archaeological proof of pre-contact burials, the mound stands as a silent testament that Fredericksburg's waterfront was alive with Native presence long before the town's founding, and that those voices still echo if one knows how to listen.

Living Heritage: The site serves as a reminder that Native American sacred sites are not merely archaeological curiosities but living heritage sites that continue to hold spiritual significance for descendant communities. The artifacts found here—pottery sherds, stone tools, and fire-cracked rocks—represent not just ancient technology but the spiritual practices, daily life, and cultural traditions of the Indigenous peoples who called this landscape home for thousands of years before European contact.

Regional Significance: This burial mound connects to a broader network of Native American sacred sites throughout Virginia, from the Monacan ancestral territory in Central Virginia to the Powhatan paramount chiefdom sites in the Tidewater. Together, these sites reveal a sophisticated understanding of sacred geography that integrated astronomical alignments, river systems, trade routes, and spiritual beliefs into a unified worldview that honored both the living and the dead.