Life & Land: The River's Bounty

Understanding the Ecological Foundation of Sacred Geography

A Convergence of Life

The fall line creates a unique ecological transition zone where Piedmont and Coastal Plain species intermingle. This biological richness provided the foundation for thousands of years of Indigenous seasonal gatherings, ceremonies, and sustainable resource management. The falls mark a transition from tidal, brackish waters below to fresh, fast-flowing waters above - an ecotone extraordinarily rich in resources.

River Ecosystem Landscape

The rich riparian habitat that supported diverse wildlife and human communities for millennia

Sacred Messenger

Bald eagles soar above the falls, connecting the Upper World with terrestrial realms

🌊 The Rappahannock River Habitat

Biodiversity at the Fall Line

The Rappahannock River, particularly in the Fredericksburg region, represents a transition zone between the Piedmont and Coastal Plain physiographic provinces. This section of the river is marked by rocky rapids and falls that create a unique blend of aquatic and terrestrial habitats.

These features promote high levels of oxygenation and water movement, supporting anadromous fish species such as American shad (Alosa sapidissima), hickory shad (Alosa mediocris), alewife (Alosa pseudoharengus), blueback herring (Alosa aestivalis), and striped bass (Morone saxatilis).

These species migrate from the Atlantic Ocean to spawn in the freshwater reaches of the river each spring, historically making this region a major fishing ground. The removal of the Embrey Dam in 2004 significantly improved fish passage, allowing these species to return to ancestral spawning habitats upstream of Fredericksburg for the first time in nearly a century.

🐟 FISH SPECIES OF THE RAPPAHANNOCK

Blue Catfish

Ictalurus furcatus

The largest catfish species in North America, blue catfish can grow over 100 pounds. Introduced to Virginia waters in the 1970s, they have become abundant in the Rappahannock. These bottom-feeders help control invasive species but can compete with native fish for resources.

Striped Bass

Morone saxatilis

Also known as rockfish, striped bass are anadromous fish that spawn in the Rappahannock's fresh waters. These prized game fish can live over 30 years and were a crucial food source for Indigenous peoples during spring spawning runs.

Northern Snakehead

Channa argus

An invasive species first discovered in Virginia waters in 2004, snakeheads are air-breathing fish that can survive on land for short periods. While considered a threat to native ecosystems, they are surprisingly good eating and help control other invasive species.

Alewife

Alosa pseudoharengus

One of the river herring species, alewives migrate from the ocean to spawn in fresh water. These small but abundant fish were historically harvested in great numbers during spring runs and provided essential protein for Indigenous communities.

Hickory Shad

Alosa mediocris

Similar to American shad but smaller, hickory shad are anadromous fish that return to the Rappahannock to spawn. They're known for their fighting ability when hooked and have been an important food fish for thousands of years.

American Shad

Alosa sapidissima

The largest of the river herrings, American shad were once so abundant they were called "the founding fish of America." Their spring spawning runs historically supported massive Indigenous fishing operations at the falls, with stone fish weirs channeling millions of fish into traps.

American Eel

Anguilla rostrata

These mysterious fish spawn in the Sargasso Sea but spend most of their lives in freshwater rivers like the Rappahannock. Eels can live over 40 years and were an important food source, often smoked or dried for winter storage by Indigenous peoples.

Yellow Perch

Perca flavescens

A popular panfish with distinctive yellow coloration and dark vertical stripes, yellow perch prefer cooler waters and are most active in fall and winter. They school in large numbers and provide excellent eating, making them a favorite target for both recreational and subsistence fishing.

Largemouth Bass

Micropterus salmoides

Virginia's state freshwater fish, largemouth bass are aggressive predators that prefer warm, weedy waters. They build nests in shallow areas during spring spawning and are fiercely protective of their young. These fish have been important to both Indigenous peoples and modern anglers.

Bluegill Sunfish

Lepomis macrochirus

One of the most common sunfish species, bluegills are small but abundant panfish that inhabit quiet backwaters and coves. They're excellent eating and easily caught, making them an important food source for families throughout history. Males build distinctive circular nests in shallow water during spawning season.

🦫 Riverine and Riparian Fauna

Aquatic Life and Terrestrial Interactions

White-tailed Deer

These graceful mammals frequent the riparian forests and were a crucial resource for Indigenous communities at river crossings near the falls

The river's shallow riffles, deep pools, wooded banks, and adjacent wetlands support a wide range of species. Aquatic invertebrates such as freshwater mussels (Unionidae), crayfish (Cambaridae), and aquatic insect larvae contribute to water filtration and serve as food sources for larger species.

Amphibians like northern dusky salamanders and green frogs rely on the clean, oxygen-rich streams, while reptiles such as eastern river cooters and northern water snakes inhabit the banks and backwaters.

Terrestrial wildlife is equally diverse. White-tailed deer, raccoons, gray foxes, and opossums frequent the riparian forest zones. Black bears may be encountered occasionally in more remote tracts, especially near large protected woodlands.

Bird species are abundant: great blue herons, belted kingfishers, wood ducks, osprey, and bald eagles all use the river corridor for feeding and nesting. Seasonal migration brings additional diversity to the bird population, making the area ecologically significant both regionally and continentally.

🦝 MAMMALS OF THE RAPPAHANNOCK CORRIDOR

American Black Bear

Ursus americanus

Virginia's largest predator, black bears frequent the forested river corridors. They're omnivores that feed on berries, nuts, fish, and small mammals. These powerful animals were revered by Indigenous peoples and played important roles in ceremonies and mythology. Bears are excellent swimmers and often fish in the river during spawning runs.

Virginia Opossum

Didelphis virginiana

North America's only native marsupial, opossums are highly adaptable nocturnal creatures. They're excellent climbers and swimmers, often foraging along riverbanks for crayfish, frogs, and fallen fruit. Despite their fearsome appearance when threatened, they're gentle animals that rarely bite and are immune to most snake venoms.

Gray Fox

Urocyon cinereoargenteus

The only American fox that can climb trees, gray foxes are secretive nocturnal hunters. They prefer forested areas near water and hunt small mammals, birds, and fish. Their excellent climbing ability allows them to escape predators and access bird nests. Indigenous peoples valued their beautiful pelts and considered them symbols of cunning and intelligence.

Red Fox

Vulpes vulpes

Intelligent and adaptable, red foxes are skilled hunters that prefer open meadows near forest edges. They hunt mice, rabbits, birds, and will scavenge fish along riverbanks. Red foxes are known for their elaborate hunting techniques, including "mousing" - listening for rodents under snow and pouncing precisely on their location.

Raccoon

Procyon lotor

Highly intelligent and dexterous, raccoons are excellent fishers and foragers. Their sensitive hands allow them to feel for crayfish, mussels, and fish in muddy water. Raccoons were important to Indigenous peoples both as food and for their fur, and their distinctive black mask made them figures in many tribal stories about trickster spirits.

Big Brown Bat

Eptesicus fuscus

One of the most common bats in Virginia, big brown bats are important insect controllers that hunt over water surfaces. They consume thousands of mosquitoes and other insects each night, helping keep pest populations in check. These bats often roost in tree cavities near the river and emerge at dusk to hunt.

Little Brown Bat

Myotis lucifugus

These small bats are incredibly efficient hunters, capable of catching over 1,000 mosquitoes per hour. They prefer to hunt over water where insects are abundant. Unfortunately, little brown bats have been severely impacted by white-nose syndrome, a fungal disease that has devastated bat populations across North America.

Muskrat

Ondatra zibethicus

Semi-aquatic rodents that build distinctive dome-shaped lodges in marshes and quiet backwaters. Muskrats are excellent swimmers and feed primarily on cattails and other aquatic vegetation. Their fur was highly prized by Indigenous peoples and early European traders. They play a crucial role in wetland ecosystems.

North American Beaver

Castor canadensis

Nature's engineers, beavers create wetland habitats that benefit countless other species. Once nearly extinct in Virginia due to overhunting, they're making a comeback in the Rappahannock watershed. Beaver dams create pools that provide fish habitat and flood control. Indigenous peoples considered beavers master builders and incorporated them into creation stories.

Bobcat

Lynx rufus

Virginia's most common wild cat, bobcats are solitary predators that hunt rabbits, rodents, and birds. They're excellent climbers and swimmers, sometimes hunting fish and frogs near water. Bobcats are elusive and rarely seen, but their tracks and scat indicate they're more common than most people realize. They were important in Indigenous hunting traditions and spiritual practices.

North American River Otter

Lontra canadensis

Playful and highly aquatic, river otters are expert fishers that can close their nostrils and ears underwater. They were extirpated from Virginia by the 1970s but have been successfully reintroduced. Otters are indicators of healthy aquatic ecosystems and were considered sacred animals by many Indigenous tribes, associated with joy, curiosity, and the spirit of flowing water.

🐢 REPTILES & AMPHIBIANS

Common Snapping Turtle

Chelydra serpentina

The largest freshwater turtle in Virginia, snappers are ancient survivors that can live over 100 years. They're omnivorous bottom-dwellers that help keep waterways clean by consuming dead fish and vegetation. Despite their fierce reputation, they're generally docile underwater and only become aggressive when threatened on land. Indigenous peoples used their shells for tools and ceremonial purposes.

Eastern Copperhead

Agkistrodon contortrix

Virginia's most common venomous snake, copperheads are ambush predators that feed on rodents, frogs, and birds. They're excellent swimmers and often hunt along riverbanks. While venomous, copperheads are generally docile and bites are rarely fatal to humans. In Indigenous traditions, snakes were often seen as guardians of sacred places and symbols of healing and transformation.

Eastern Box Turtle

Terrapene carolina carolina

Virginia's state reptile, box turtles are terrestrial but often found near water sources. They can live over 100 years and have excellent homing abilities, often returning to the same small territory throughout their lives. Box turtles are omnivores that help disperse seeds throughout the forest. Their shells were traditionally used by Indigenous peoples for containers, rattles, and ceremonial objects.

🦋 INSECTS & INVERTEBRATES

Big Sandy Crayfish

Cambarus veteranus

These large freshwater crustaceans are important indicators of water quality and serve as food for fish, birds, and mammals. Crayfish are ecosystem engineers that help aerate sediments and process organic matter. They were harvested by Indigenous peoples and remain a popular food source today. Their molted shells provide calcium for the aquatic food web.

Fireflies

Photinus spp.

These magical insects create summer's most enchanting displays along the river corridors. Firefly larvae are beneficial predators that feed on snails and other soft-bodied insects. Adults use bioluminescence for mating displays, with each species having its own unique flash pattern. Indigenous peoples saw fireflies as spirits of ancestors and messengers between worlds.

Black Widow Spider

Latrodectus mactans

While venomous and potentially dangerous, black widows are important predators that control insect populations. They prefer dark, undisturbed areas near water and are generally reclusive. Bites are rare and usually occur when the spider is accidentally disturbed. In traditional stories, spiders were often portrayed as wise weavers who taught humans important skills.

Monarch Butterfly

Danaus plexippus

These iconic butterflies undertake incredible migrations, traveling thousands of miles between Canada and Mexico. Monarchs depend on milkweed plants for reproduction and serve as important pollinators. Their decline has become a symbol of environmental challenges facing wildlife. Many Indigenous cultures saw butterflies as symbols of transformation, resurrection, and the soul's journey.

🦅 BIRD SPECIES OF THE RAPPAHANNOCK

Bald Eagle

Haliaeetus leucocephalus

America's national bird has made a remarkable recovery along the Rappahannock. These powerful raptors are primarily fish-eaters and are often seen hunting near the falls during fish runs. Bald eagles were sacred to Indigenous peoples, representing connection between earth and sky, and their feathers were used in the most sacred ceremonies.

Osprey

Pandion haliaetus

Specialized fish hawks, ospreys have incredible eyesight and dive feet-first to catch fish. They build large stick nests on platforms or dead trees near water. After DDT nearly caused their extinction, osprey populations have rebounded thanks to conservation efforts. They migrate thousands of miles between North and South America each year.

Wood Duck

Aix sponsa

Considered one of North America's most beautiful waterfowl, wood ducks nest in tree cavities near water. Ducklings must leap from high nests to water shortly after hatching. These ducks were nearly extinct by 1900 but have recovered through conservation efforts and nest box programs. They feed on acorns, seeds, and aquatic invertebrates.

Belted Kingfisher

Megaceryle alcyon

These stocky birds are expert fishers that dive headfirst into water to catch small fish. They excavate burrows in riverbanks for nesting and have a distinctive rattling call. Unusually among birds, female kingfishers are more colorful than males. Indigenous peoples associated kingfishers with prosperity and good fishing.

Great Blue Heron

Ardea herodias

The largest heron in North America, these patient hunters wade in shallow water waiting to spear fish, frogs, and small mammals. They're excellent fliers despite their size and often nest in colonies called rookeries. Great blue herons are symbols of patience and self-reliance in many Indigenous traditions.

Pileated Woodpecker

Dryocopus pileatus

The largest woodpecker in North America, pileateds create large rectangular holes in dead trees while hunting for carpenter ants. Their excavations create nesting sites for many other species. These impressive birds need large territories of mature forest and are indicators of healthy forest ecosystems.

Northern Cardinal

Cardinalis cardinalis

Virginia's state bird, cardinals are year-round residents known for their beautiful song and bright red plumage (in males). They're seed-eaters that frequent bird feeders and forest edges. Cardinals mate for life and both parents care for their young. Their presence is often seen as a sign of good luck or a visit from deceased loved ones.

American Crow

Corvus brachyrhynchos

Highly intelligent and social birds, crows are omnivores that adapt well to human presence. They use tools, remember faces, and have complex social structures. Crows play important ecological roles as scavengers and seed dispersers. In many Indigenous cultures, crows are seen as messengers and symbols of transformation.

Common Raven

Corvus corax

Larger and more robust than crows, ravens prefer wilder areas and are excellent fliers capable of aerial acrobatics. They're among the most intelligent birds and can live over 20 years. Ravens feature prominently in Indigenous mythology as creators, tricksters, and guides between worlds. Their calls are deeper and more varied than crows.

Red-tailed Hawk

Buteo jamaicensis

One of the most common raptors in North America, red-tailed hawks hunt small mammals from perches or while soaring. They're adaptable birds that can thrive in various habitats from forests to urban areas. Their distinctive call is often used in movies for any raptor. In Indigenous traditions, hawks represent vision, protection, and connection to spiritual realms.

Double-crested Cormorant

Phalacrocorax auritus

Expert underwater hunters, cormorants dive deep to catch fish and can stay submerged for over a minute. Their feathers are not fully waterproof, so they're often seen spreading their wings to dry. These colonial nesters were once threatened by DDT but have made a strong recovery and are now common on the Rappahannock.

Blue Jay

Cyanocitta cristata

Intelligent and social members of the corvid family, blue jays are known for their loud calls and aggressive behavior toward potential threats. They're important seed dispersers, especially for oak trees, and can live over 20 years. Blue jays are excellent mimics and can imitate the calls of other birds, particularly hawks.

Cooper's Hawk

Accipiter cooperii

Agile forest hawks that specialize in hunting birds, Cooper's hawks navigate through dense woods with remarkable skill. They're ambush predators that often hunt near bird feeders. These raptors have rebounded from DDT-related population declines and are now adapting well to suburban environments.

Ruby-throated Hummingbird

Archilochus colubris

The only hummingbird that regularly breeds in eastern North America, these tiny birds are remarkable migrants that cross the Gulf of Mexico twice yearly. They can hover, fly backwards, and beat their wings up to 80 times per second. Hummingbirds are important pollinators and are seen as symbols of joy, healing, and good luck in many cultures.

Canada Goose

Branta canadensis

Large waterfowl known for their distinctive honking calls and V-shaped flight formations. Canada geese are grazers that feed on grasses, aquatic plants, and agricultural crops. They mate for life and are highly protective of their young. Once threatened by overhunting, they've recovered so well they're now considered overabundant in some areas.

Barn Owl

Tyto alba

Silent nocturnal hunters with exceptional hearing, barn owls can locate prey in complete darkness. They're beneficial predators that consume large numbers of rodents. Their heart-shaped facial disc helps funnel sound to their ears. Barn owls nest in cavities and have declined due to habitat loss and modern farming practices.

Great Horned Owl

Bubo virginianus

Powerful nocturnal predators with excellent night vision and hearing, great horned owls hunt a wide variety of prey from mice to skunks. They're early nesters, often taking over hawk or crow nests in winter. Their distinctive "hoot" is a classic sound of American nights. Indigenous peoples associated owls with wisdom, protection, and messages from the spirit world.

American Robin

Turdus migratorius

One of the most familiar North American birds, robins are often considered harbingers of spring. They're ground foragers that hunt earthworms and insects by sight and sound. Robins are partial migrants - some populations migrate while others remain year-round. Their cheerful song and red breast have made them symbols of renewal and hope.

Wild Turkey

Meleagris gallopavo

Large ground birds that were nearly extinct by 1900 but have made a remarkable recovery. Wild turkeys are excellent fliers despite their size and roost in trees at night. They're omnivores that feed on nuts, seeds, insects, and small reptiles. Turkeys were extremely important to Indigenous peoples for food, feathers, and ceremonial purposes, and almost became America's national bird.

⏳ HISTORIC SPECIES - Lost to Time

These magnificent animals once roamed the Rappahannock region but have been lost to extinction through habitat destruction, overhunting, and human expansion.

Gray Wolf

Canis lupus

Extinct in Virginia: ~1900

Once the apex predator of Virginia's forests, gray wolves were systematically hunted to extinction as European settlement expanded. The last wolves in Virginia were killed in the early 1900s. These intelligent pack hunters were revered by Indigenous peoples as teachers and spiritual guides, featuring prominently in tribal mythology and clan systems.

Eastern Cougar

Puma concolor couguar

Extinct in Virginia: ~1880s

The last eastern cougar in Virginia was reportedly killed in the 1880s, though some believe they persisted into the early 1900s. These powerful solitary cats were feared and respected by both Indigenous peoples and European settlers. Cougars were symbols of strength and stealth in Native American traditions.

American Bison

Bison bison

Extinct in Virginia: ~1800

Eastern bison once grazed in the meadows and river valleys of Virginia, including areas near the Rappahannock. They were hunted to local extinction by the early 1800s. These massive herbivores were sacred to Indigenous peoples and provided food, clothing, shelter, and spiritual connection to the land.

Eastern Elk

Cervus canadensis canadensis

Extinct in Virginia: ~1850s

Once abundant in Virginia's forests and meadows, eastern elk were larger than their western cousins. The last wild elk in Virginia was killed in the 1850s. Their bugling calls once echoed through river valleys, and they were important game animals for Indigenous peoples. Today, a small population of western elk has been reintroduced to southwestern Virginia.

Carolina Parakeet

Conuropsis carolinensis

Extinct globally: 1918

The only native parrot of the eastern United States, Carolina parakeets were colorful, social birds that lived in flocks. They were found throughout Virginia until the late 1800s. Habitat destruction and hunting for their beautiful feathers led to their extinction. The last wild bird was seen in 1910, and the last captive bird died in 1918.

American Pine Marten

Martes americana

Extinct in Virginia: ~1950s

These cat-sized members of the weasel family were once found in Virginia's mountain forests. Overhunting for their valuable fur and habitat destruction led to their extirpation by the mid-1900s. Pine martens were skilled climbers that hunted squirrels and birds in the forest canopy. Small reintroduction efforts are being considered for suitable habitat.

🧊 ICE-AGE MEGAFAUNA - Ancient Giants

During the Pleistocene epoch (2.6 million - 11,700 years ago), the Rappahannock region was home to massive creatures that would seem mythical today. These megafauna disappeared around 10,000-8,000 BCE due to climate change and human hunting pressure.

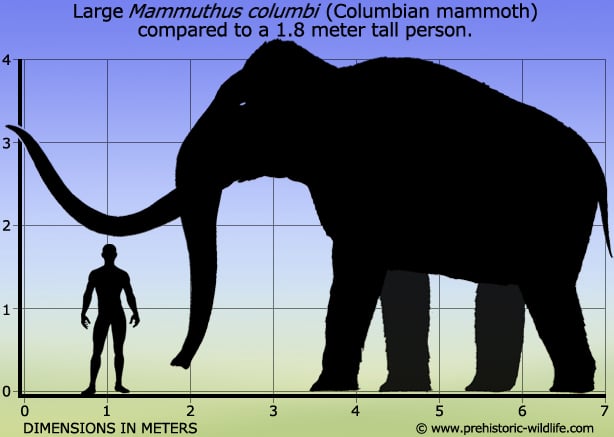

Columbian Mammoth

Mammuthus columbi

Extinct: ~10,000 BCE

Larger than modern elephants, Columbian mammoths stood up to 14 feet tall and weighed 10 tons. These giants browsed the forests and meadows near ancient rivers. Mammoth remains have been found throughout Virginia, and Indigenous oral traditions may preserve memories of these magnificent creatures as "great hairy elephants" in creation stories.

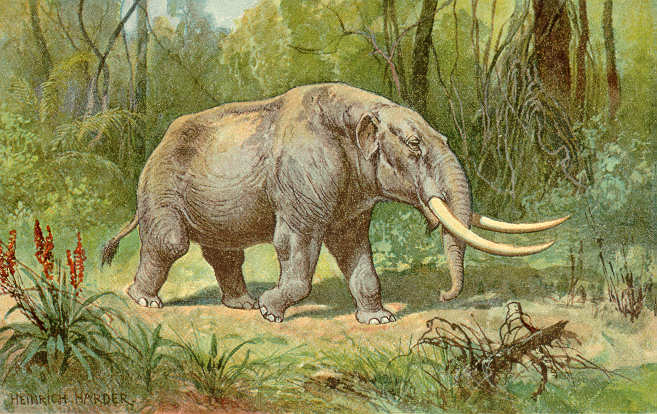

American Mastodon

Mammut americanum

Extinct: ~10,000 BCE

Smaller than mammoths but still massive, mastodons were forest dwellers that fed on twigs and leaves. Multiple mastodon fossils have been discovered in Virginia, including teeth found near the Rappahannock watershed. These creatures may have gathered at river crossings, making them vulnerable to human hunters.

.png)

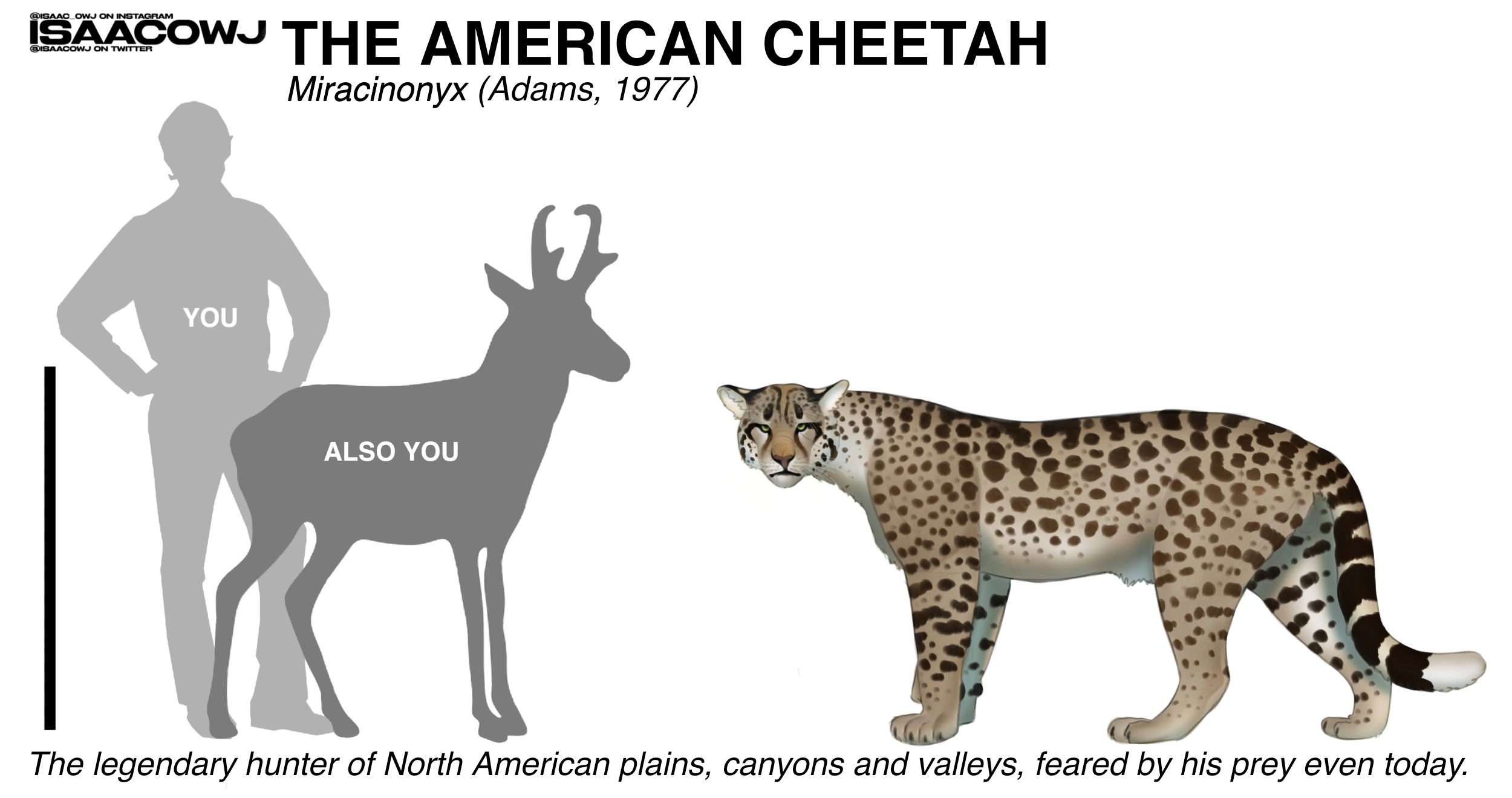

American Cheetah

Miracinonyx trumani

Extinct: ~10,000 BCE

Despite the name, these were not true cheetahs but large cats adapted for speed. American cheetahs likely hunted pronghorn antelope across open landscapes. They may have prowled river valleys hunting deer and other prey. These swift predators could explain why pronghorns today can run 70 mph - they evolved to escape a predator that no longer exists.

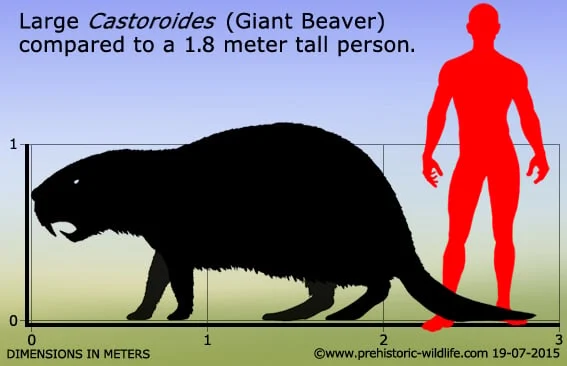

Giant Beaver

Castoroides ohioensis

Extinct: ~10,000 BCE

The size of a black bear, giant beavers were the largest rodents ever to live in North America. Unlike modern beavers, they probably didn't build dams but lived in riverbank burrows. Giant beaver fossils have been found in eastern river systems, and they likely inhabited the ancient Rappahannock. Indigenous stories of giant water creatures may remember these massive engineers.

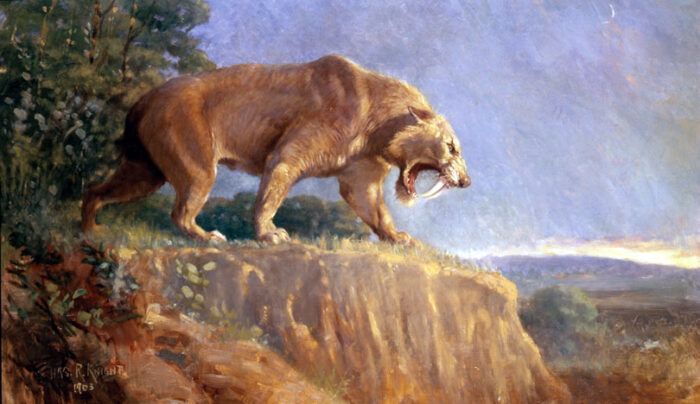

Saber-tooth Cat

Smilodon fatalis

Extinct: ~10,000 BCE

Armed with 7-inch canine teeth, saber-tooth cats were powerful predators that hunted large prey like young mammoths and giant ground sloths. These cats were built for ambush hunting near water sources where prey animals gathered. Their distinctive dental weapons made them legendary apex predators of the Ice Age.

Ancient Bison

Bison latifrons

Extinct: ~20,000 BCE

Much larger than modern bison, these giant bovines had horns spanning 8 feet from tip to tip. Ancient bison roamed the grasslands and river valleys of Ice Age Virginia. They were succeeded by smaller bison species that survived until historical times. Paleo-Indian hunters targeted these massive herbivores, and projectile points have been found with bison remains.

🦴 Archaeological + Fossil Evidence in VA

• Mastodon teeth found in Isle of Wight and Loudoun Counties

• Mammoth molars recovered in the Coastal Plain and Piedmont

• Giant beaver fossils in the eastern U.S. river systems, including Chesapeake lowlands

• Projectile points (Clovis, Hardaway) linked to megafauna hunting

🌀 Spiritual + Mythic Connections

Many Virginia Native American myths and oral traditions speak of giant beasts, underworld creatures, and great hunters. These may be cultural memories of Ice Age megafauna passed down through deep time, preserved in stories told around fires for thousands of years.

🧠 WHAT HAPPENED TO THEM?

• Climate shift at the end of the Ice Age radically altered ecosystems

• Human hunting by Paleo-Indians (like the Clovis peoples) contributed to pressure on large mammal populations

• Combined stresses led to a rapid extinction wave around 10,000–8,000 BCE

🏞️ Human Dependence and Indigenous Knowledge

Cultural and Environmental Interconnection

For thousands of years, Indigenous peoples such as the Rappahannock and related Algonquian-speaking tribes relied on the river not only for sustenance but also as a spiritual and social cornerstone. The seasonal fish migrations provided predictable and abundant food supplies, while river-adjacent forests and meadows offered game, wild plants, and medicinal herbs.

The river served as a transportation route and a central location for community gathering and ceremony. Archaeological evidence from the region supports long-term human habitation and resource use, particularly near the fall line where fish would naturally congregate.

Today, the same ecological functions that sustained native communities continue to provide essential benefits to modern populations. The Rappahannock River supplies drinking water, supports local agriculture, buffers flood events, and offers recreational opportunities.

Its biodiversity contributes to pollination, pest control, and ecological resilience in the face of climate change. Preserving the river's ecological integrity is not just a matter of conservation—it is an investment in regional health, heritage, and sustainability.

Seasonal Abundance Cycles

The falls introduced an element of unpredictability – sudden floods from storms would make the river "quick rising" (indeed "Rappahannock" in Algonquian means "river of quick, rising water"). This volatility likely enhanced the river's sacred status, while the balance of habitats furnished everything a community needed.

🌸 Spring: The Great Fish Runs

Massive runs of shad, herring, striped bass, and sturgeon congregated below the rapids. Indigenous communities constructed stone fish weirs to funnel fish into traps, accompanied by First Fish ceremonies to honor the spirits.

☀️ Summer: River Community

Extended families established seasonal camps along the banks. The rich riparian habitat supported diverse wildlife - great blue herons, ospreys, eagles, and abundant forest species provided continuous sustenance.

🍂 Fall: Harvest Gatherings

Oak and hickory forests provided abundant nuts. Deer crossed at shallow spots near the falls, making it ideal for communal hunting drives that brought together multiple communities.

❄️ Winter: Sacred Reflection

While communities moved to inland hunting camps, the falls remained a place for vision quests and spiritual retreats, where shamans sought guidance in the stark winter landscape.

🌊 Water and Environmental Cycles

Sacred Waters - The dynamic flow of water through the landscape created diverse habitats and spiritual opportunities

The falls concentrated water flow into strong currents and quieter eddies, creating diverse microhabitats. During low water periods (summer droughts), many more rocks and carvings become accessible, while high water brings spawning fish and celebrates the floodwaters. This dynamic accessibility had profound ritual implications.

The ready availability of large quartzite and granite cobbles at the falls made it easy to construct fish weirs - low walls to funnel fish. Indigenous inhabitants likely maintained these seasonally, becoming intimately familiar with each rock, pool, and alcove, naming them and mythologizing them.

PLANTS & TREES OF THE RAPPAHANNOCK

Virginia Creeper

Parthenocissus quinquefolia

Found climbing trees and rock walls along riverbanks and forest edges, Virginia Creeper is a fast-growing native vine known for its five-leaflet arrangement and brilliant red fall color. It produces small dark berries in late summer that are toxic to humans ⚠️ but are a food source for birds. While not edible, its vines have historically been used for weaving and basketry. It grows rapidly and is useful for erosion control along riparian slopes.

River Birch

Betula nigra

Commonly found on moist floodplains and riverbanks, River Birch thrives in the wet, shifting soils near the Rappahannock. Recognizable by its peeling salmon-colored bark, this tree grows quickly and provides essential habitat for birds and insects. Though not typically used as food, its inner bark is technically edible in survival situations, and it has been used traditionally for small tools, cordage, and canoes.

Passionflower

Passiflora incarnata

Often growing in sunny clearings and field edges near the river, this vine produces intricate purple flowers and small fruit known as maypops. The fruit is edible and high in nutrients, and parts of the plant have been used medicinally for centuries as a natural sedative and anti-anxiety remedy. It dies back in winter but regrows from the roots in spring, spreading via runners.

Black Walnut

Juglans nigra

Thriving in rich, well-drained soils near the river and bottomlands, Black Walnut is a large deciduous tree known for its dark, ridged bark and round green husked nuts. The nuts are edible but tough to extract, and the husks yield a deep brown dye. Black walnut trees release juglone, a natural herbicide that suppresses growth of nearby plants, and all parts of the plant can irritate skin ⚠️.

Hickory

Carya spp.

Several species of hickory grow in the Rappahannock lowlands and hills, especially in dry upland forests near the river corridor. These slow-growing hardwood trees produce edible nuts, though many are bitter. Hickory wood is prized for tool handles, furniture, and firewood due to its density and burn time. Indigenous communities also used hickory milk—a mash of nut and water—as a protein-rich drink.

Oak Trees & Acorns

Quercus spp.

Dominating much of the upland forest surrounding the river, oak trees are keystone species in the Rappahannock ecosystem. Their acorns, though bitter due to tannins, were leached and ground by Native peoples to make flour. Oaks support an immense range of wildlife—over 500 species of caterpillars alone—and their wood has been used historically for structures, barrels, and tools.

Sassafras

Sassafras albidum

This aromatic shrub or small tree is common along field edges and sandy soils near the river. Its distinctive three-lobed leaves and spicy scent make it easy to identify. Sassafras root was traditionally used by Native peoples to flavor tea and treat fevers, and is a historical ingredient in root beer. However, the compound safrole found in the root bark is considered carcinogenic in large amounts ⚠️.

Virginia Persimmon

Diospyros virginiana

Often found in open woods, floodplains, and abandoned fields near the river, the Virginia Persimmon produces sweet, orange fruits in the fall. The fruit is edible only when fully ripe (otherwise astringent), and was eaten fresh or dried by Indigenous peoples. The wood is dense and durable, sometimes used for tools or golf club heads. It's an important fall food source for deer, opossum, and birds.

Mullein

Verbascum thapsus

Growing in dry, sunny clearings along roads and disturbed ground near the river, mullein is a tall biennial herb with woolly leaves and a candle-like flowering stalk. While not native, it has naturalized across the region. Its leaves and flowers were used traditionally for respiratory ailments (steeped as tea), and the soft leaves were used as poultices or even toilet paper. Not considered toxic, but ingestion in large quantities should be avoided ⚠️.

Cattails

Typha latifolia

Abundant in marshy areas and slow backwaters of the Rappahannock, cattails are one of the most useful wild plants. Nearly every part is edible at some stage—young shoots, pollen, roots—and was used by Indigenous communities for food and weaving materials. Cattails also provide important shelter and nesting habitat for birds and amphibians, and help purify water by filtering out sediments and pollutants.

Poison Sumac ⚠️

Toxicodendron vernix

This plant is found in swampy, saturated soils along the river's floodplain. Easily confused with other shrubs, it has smooth-edged compound leaves and produces white berries. All parts of the plant contain urushiol, the same toxic oil found in poison ivy, and can cause severe skin irritation upon contact. It should be avoided at all times and never burned, as inhalation of the smoke is dangerous.