The Colonial Transformation

From Sacred Ground to Colonial Settlement

The establishment of Fredericksburg in 1728 marked the complete transformation of the sacred Rappahannock fall line from Indigenous ceremonial landscape to European colonial and industrial center. Yet beneath this overlay, the ancient sacred sites persisted, waiting for recognition and renewed reverence.

🏺 Pre-Colonial & Native History

The Deep History of the Sacred Fall Line

c. 15,000-13,000 years ago: Ice Age Arrival

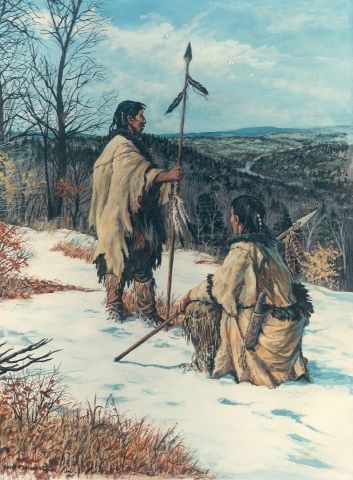

The first Virginians, known as the Clovis people, arrive during the late Ice Age. These Paleo-Indian hunters followed mega-fauna across the land bridge and began the first human occupation of the Rappahannock corridor. Their distinctive fluted spear points mark the beginning of continuous Indigenous presence at the fall line.

8000-1000 BCE: Archaic Period

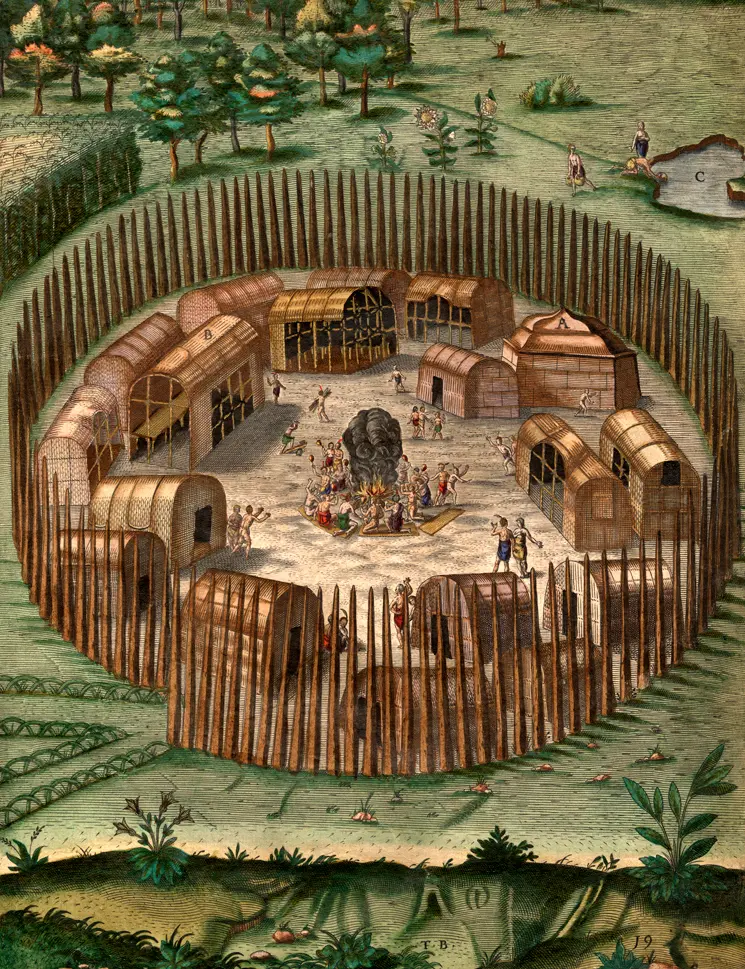

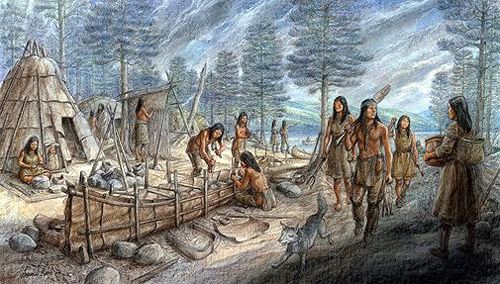

During this long period, Indigenous peoples developed sophisticated seasonal rounds, utilizing the fall line's rich resources. Archaeological evidence suggests intensive use of the rapids for fishing weirs and processing camps. The sacred geography of the fall line begins to take shape as spiritual practices become tied to the convergence of earth and water energies.

1000 BCE-900 CE: Early Woodland Period

The introduction of pottery and more complex settlement patterns marks this era. Archaeological finds in the Rappahannock corridor include burial sites and village locations that demonstrate the growing spiritual significance of the fall line. The Snake Rock and other sacred sites likely gain their ceremonial importance during this period.

c. 1545: Birth of Wahunsenacawh (Powhatan)

The future paramount chief of the Powhatan Confederacy is born. His leadership would transform the political landscape of tidewater Virginia and establish the confederacy that would control the sacred fall line sites for generations.

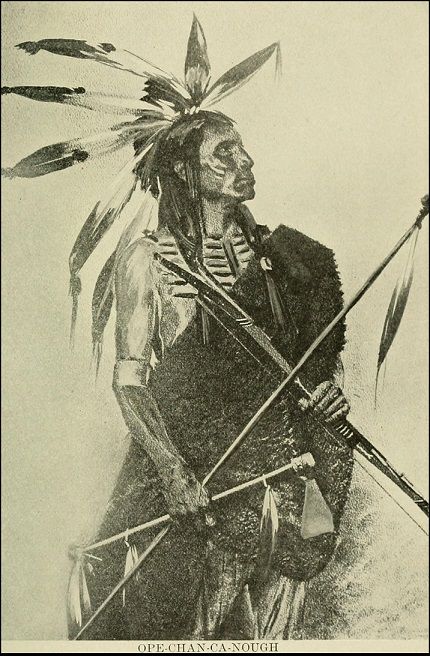

c. 1544: Birth of Opechancanough

Powhatan's brother and eventual successor is born. Opechancanough would lead the most determined resistance to colonial expansion, fighting to preserve Indigenous control over sacred sites including the Rappahannock fall line.

Late 16th Century: Birth of Kekataugh

Powhatan's brother and ruler of the village of Pamunkey is born. His leadership of this strategic village near the fall line demonstrates the continued importance of these sacred sites in Indigenous political structure.

Late 16th Century: Birth of Jappazaws

Another brother of Powhatan, Jappazaws (Anglicized as Iopassus) is the Weroance, or commander, of the Patawomeck tribe, extending Powhatan influence northward and helping to create a network of allied tribes controlling multiple fall line sites throughout the region.

Mid-1570s: Formation of the Powhatan Confederacy

Wahunsenacawh unites over 30 Algonquian-speaking tribes into the powerful Powhatan Confederacy. This political alliance gives the paramount chief control over the sacred fall line sites and establishes the confederacy's authority over the spiritual landscape that European colonists would later encounter.

1560s-1580s: Monacan vs Powhatan at Natural Bridge

Ongoing conflicts between the Monacan peoples and Powhatan's expanding confederacy reach their climax in battles near Natural Bridge. These wars establish Powhatan dominance over the fall line region and secure Indigenous control over the sacred sites that would later become Fredericksburg.

c. 1596: Birth of Pocahontas (Matoaka)

The daughter of Powhatan is born, who would become the most famous bridge between Indigenous and European worlds. Her later marriage to John Rolfe would temporarily preserve peace and protect the sacred sites from immediate colonial encroachment.

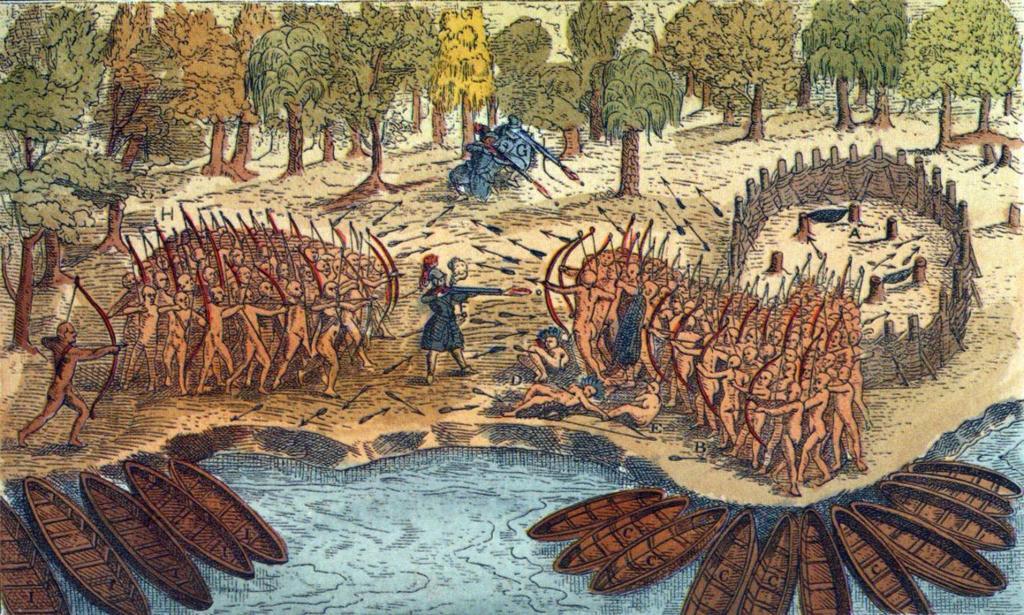

1608: Amorolek vs John Smith

The confrontation between Manahoac weroance Amorolek and Captain John Smith at the Rappahannock fall line marks the first recorded conflict between Europeans and the guardians of the sacred sites. This encounter represents the beginning of the end for Indigenous control over the spiritual landscape.

c. 1618: Death of Powhatan

The death of the great paramount chief Wahunsenacawh around 1618 marks the end of an era. His passing removes the diplomatic restraint that had maintained the fall line as neutral sacred ground. Power passes to his brother Opitchapam and then to the more militant Opechancanough, setting the stage for the coming wars that would determine the fate of the sacred sites.

⚔️ American Colonial History

European Contact and the Struggle for Control

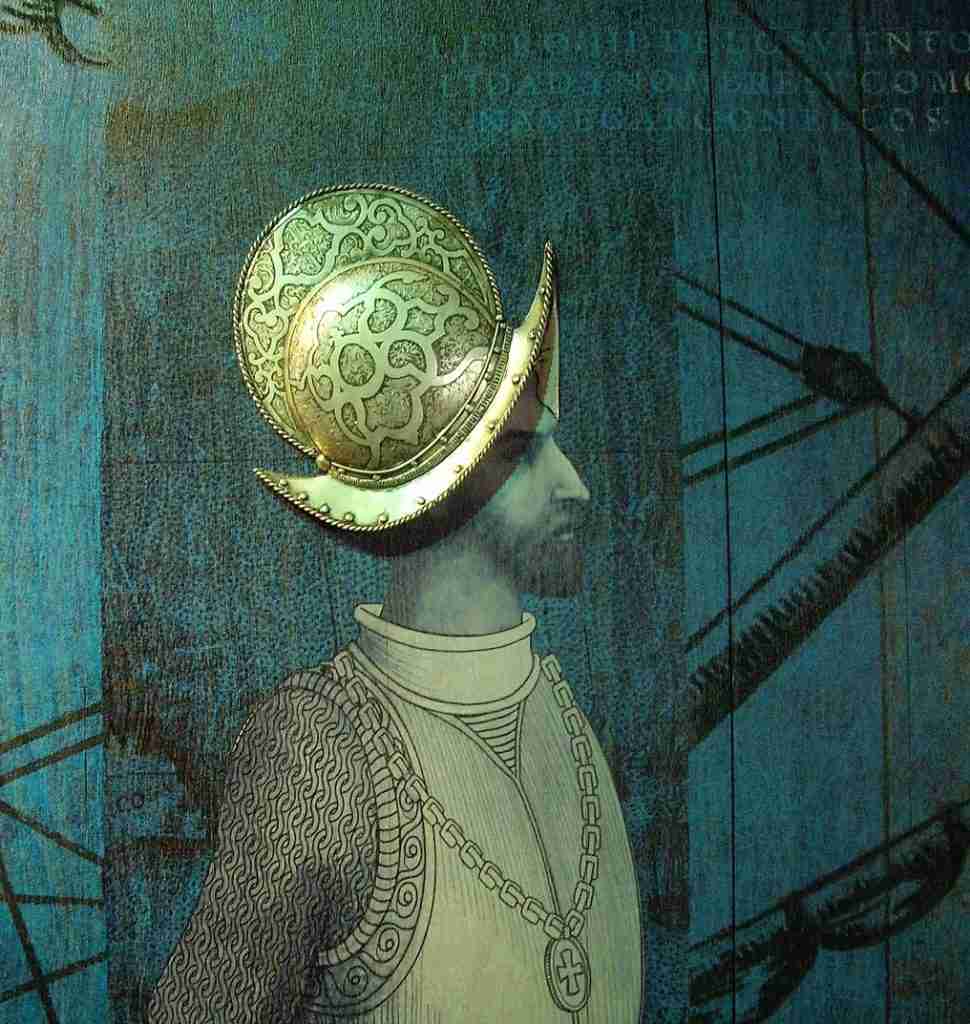

1492: Columbus's Voyage to the Americas

Christopher Columbus's arrival in the Caribbean sets in motion the European colonization that would eventually reach Virginia's sacred fall line sites. This moment begins the transformation that would culminate in the destruction of Indigenous control over the Rappahannock corridor.

1540: Early Spanish Expeditions

Under Hernando de Soto's broader expedition, Juan de Villalobos and Francisco de Silvera lead the first European exploration into Virginia territory. These early Spanish incursions demonstrate European interest in the region's resources, though they do not yet threaten the sacred sites directly.

1567: Luisa Mendelez Cherokee woman married to Juan Ribas Spanish Soldier at Saltville Virginia

The first recorded marriage between a European and Native American woman in Virginia territory takes place at Saltville. Luisa Mendelez, a Cherokee woman, marries Juan Ribas, a Spanish soldier, representing the earliest documented union between Indigenous and European peoples in the region, predating the more famous Pocahontas-Rolfe marriage by nearly half a century.

1567: Spanish Reach Saltville

In 1567, a Spanish force led by Hernando Moyano attacked a Native American village, then known as Maniatique, in present-day Saltville, Virginia. This attack, known as the "Moyano's Foray," is considered the first battle in Virginia's history. The Spanish force, part of an expedition led by Juan Pardo, had traveled northward from Fort San Juan near Morganton, North Carolina, searching for gold and silver. Maniatique was known for its abundant salt deposits, a valuable resource to the Yuchi people who inhabited the area. While the Spanish were interested in resource extraction, particularly precious metals, they ultimately did not find the wealth they sought in this region. This Spanish expedition mapped the territory and established European awareness of Virginia's strategic resources, setting the stage for future colonization efforts.

1570: Ajacan Mission

Spanish Jesuit missionaries establish the Ajacán Mission (also known as St. Mary's Mission) in the Chesapeake Bay region, led by Father Juan Bautista de Segura. This ambitious mission was guided by Don Luis de Velasco (originally named Paquiquineo), a Virginia Indian who had been taken to Spain in 1561, educated by Jesuits, and converted to Christianity. The mission was unusual in that it operated without military protection, as the Jesuits believed this would aid their conversion efforts.

On September 10, 1570, the missionaries landed near what would later become Jamestown, establishing their mission possibly at the Native village of Kiskiack near the York River. However, after initially helping the missionaries, Don Luis reunited with his family and gradually distanced himself from the Spanish. The mission faced severe challenges including drought, food shortages, and growing tensions with local tribes who viewed the foreign priests as threats to their traditional spiritual practices.

In February 1571, Don Luis led an attack that killed all the missionaries except for young altar boy Alonso de Olmos. This dramatic end to Virginia's first European settlement attempt—37 years before Jamestown—demonstrated Indigenous resistance to foreign religious and cultural domination. The following year, Spanish forces returned from Florida, rescued Alonso, and conducted punitive raids against local tribes. The failed Ajacán Mission represents the first systematic European attempt to transform Indigenous spiritual practices in Virginia, foreshadowing the later displacement of sacred sites by colonial religion.

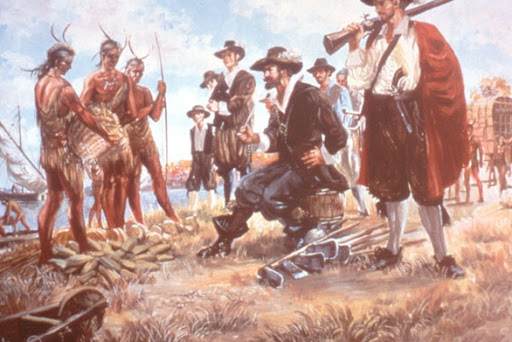

1607: Founding of Jamestown

The establishment of the first permanent English settlement in Virginia begins the process that will ultimately transform the sacred fall line from Indigenous ceremonial ground to colonial industrial site. Jamestown's survival depends on tobacco cultivation and river commerce, creating economic pressures that will drive expansion up the Rappahannock.

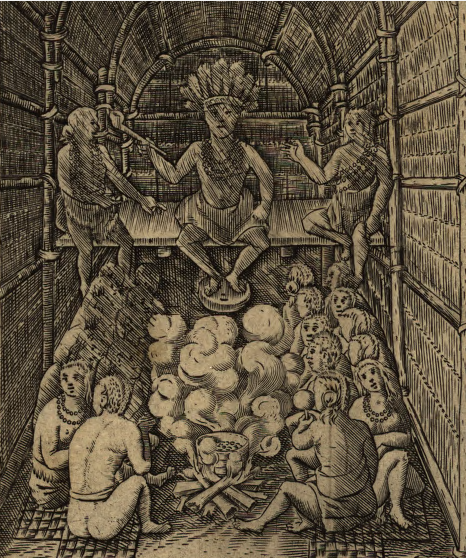

1607: Werowocomoco

Captain John Smith visits Powhatan's capital at Werowocomoco, beginning the diplomatic relationship that would initially protect the sacred sites. These early encounters establish the political framework within which Indigenous control over the fall line would be gradually eroded.

1608: Smith's Expedition to the Falls

John Smith's voyage up the Rappahannock brings the first recorded European encounter with the sacred fall line sites. His confrontation with Amorolek marks the beginning of European awareness of the spiritual significance of these locations and the start of the process that would transform them.

1609-1614: First Anglo-Powhatan War

The conflict began when Chief Powhatan attempted to control English expansion through siege warfare. The famous "Starving Time" winter of 1609-1610 nearly destroyed the Jamestown colony, but English reinforcements arrived in spring 1610. The war ended with the marriage of Pocahontas to John Rolfe in 1614, creating a fragile peace that lasted until Powhatan's death.

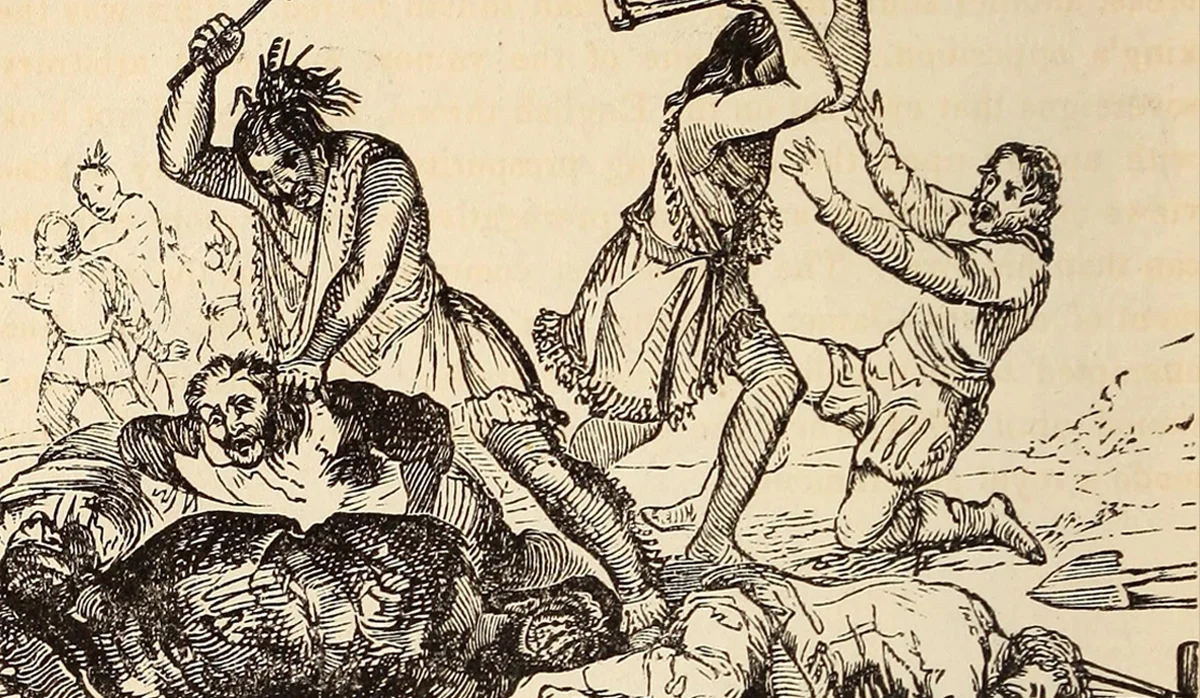

1622-1632: Second Anglo-Powhatan War

On March 22, 1622, Opechancanough launched a coordinated surprise attack that killed 347 colonists—nearly one-third of Virginia's population. The assault targeted settlements spreading up the James and Rappahannock rivers toward the sacred fall lines. Though devastating, the attack failed to drive out the English, and a decade of brutal warfare followed. By 1632, the balance of power had shifted permanently to the colonists.

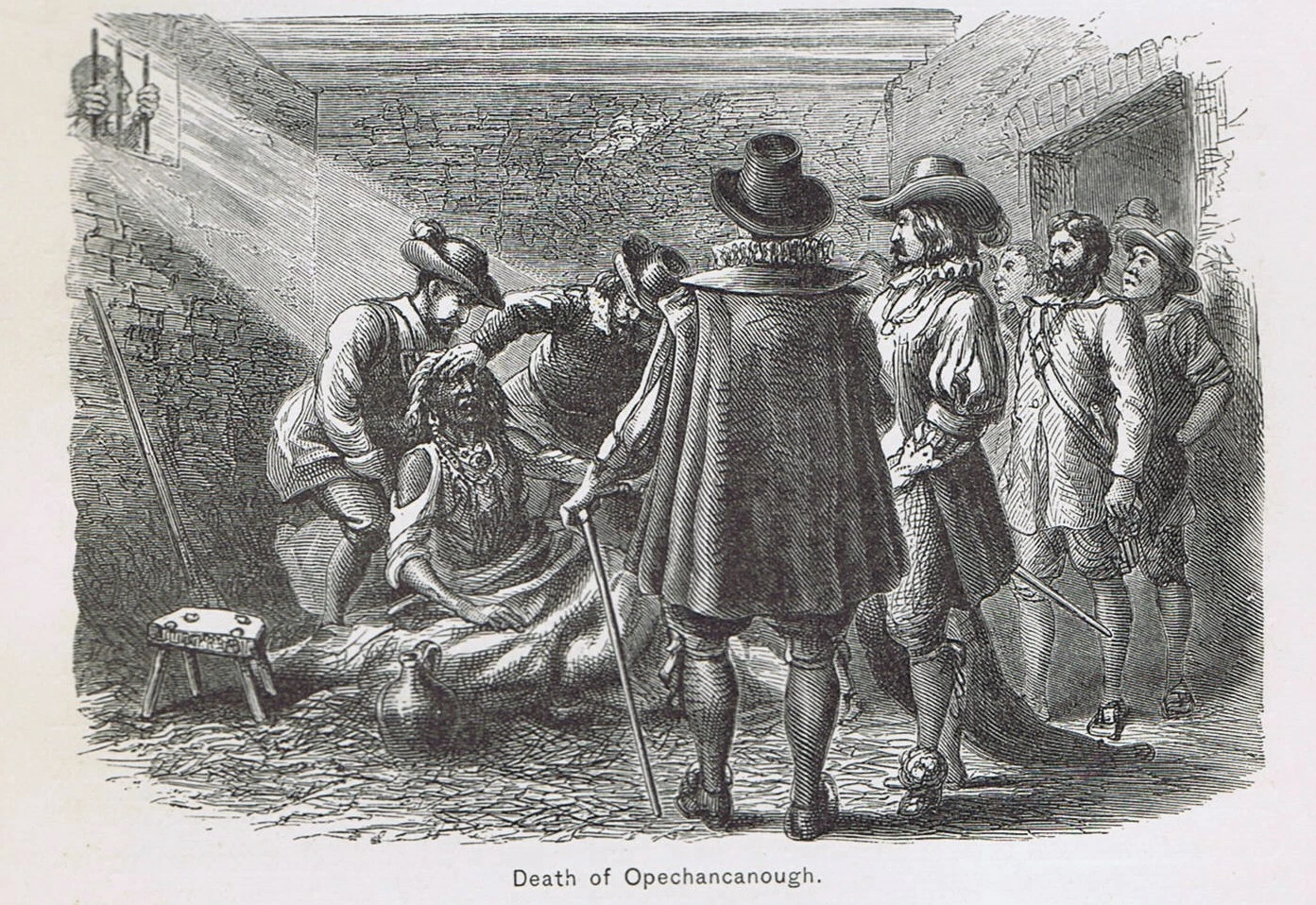

1644-1646: Third Anglo-Powhatan War

Opechancanough's final attempt to reclaim Indigenous lands began on April 18, 1644, when the nearly 100-year-old chief launched another coordinated assault, killing approximately 400 colonists. However, this now represented less than 10% of Virginia's population. The English response was swift and devastating.

1646: Death of Opechancanough

Virginia Governor William Berkeley captured the ancient chief at his stronghold on the Pamunkey River. Opechancanough was taken to Jamestown, caged, and displayed as a curiosity. Despite Berkeley's orders to keep him alive, a guard shot the legendary resistance leader in the back, ending both his life and the last organized Indigenous resistance to colonial expansion. His death opened all tribal lands, including the sacred fall line, to European settlement.

1650-1700: The Beaver Wars Impact

Iroquois raids during the Beaver Wars further decimate Piedmont tribes including the Manahoac. The sacred fall line's guardians retreat or merge with other groups, leaving the ceremonial sites undefended and vulnerable to colonial appropriation.

1728: The Final Displacement

Meanwhile, English settlers began pushing upriver. Fredericksburg was founded just below the falls in 1728 – significantly, the same year the Manahoac are last noted in records as a distinct people. The Patawomeck fared little better; encroachment and conflict led to their dispersal or assimilation by the eighteenth century (though many descendants persisted in the region, preserving their identity in private).

By the colonial period, the fall line's sacred sites and villages had been largely vacated, repurposed for mills and river commerce. Yet the memory of those indigenous inhabitants did not vanish: colonial diarists and later antiquarians recorded hints of Native towns and curiosities (like carved rocks) at the falls, keeping alive the knowledge that this landscape had been an important Indian domain.

1800s: Final Dispossession

The desire to push the Powhatan Indians off their lands began again. This time the specific target was the four remaining Virginia Indian tribes that still held onto their reservation lands. The whites also wanted to end their status as tribes. One reservation was sold by 1850 while another, the Nottoway Reservation, was divided by 1878 (though many families held onto their lands into the 20th century). The Mattaponi and Pamunkey are the only two tribes that refused to give in to the attempts and still maintain their reservations into the present day.

🏛️ Fredericksburg History

The Rise of Colonial Commerce and Industry

The Founding of Fredericksburg

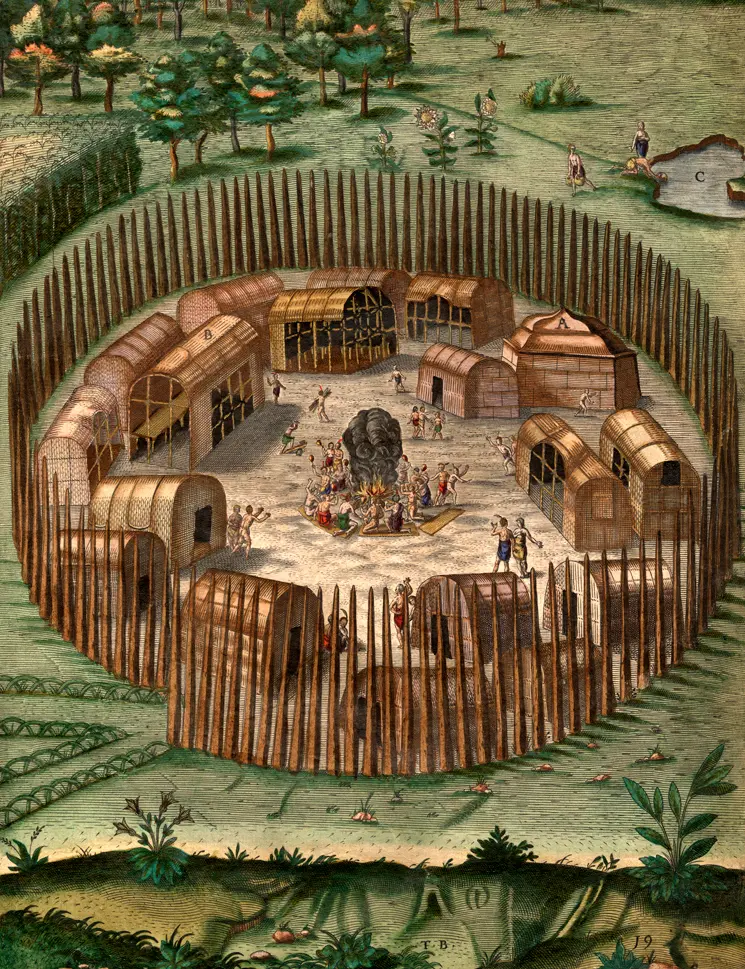

Named for Frederick, Prince of Wales, Fredericksburg was strategically positioned to take advantage of the natural fall line that had made this location sacred to Indigenous peoples for millennia. What the colonists saw as an ideal location for mills and commerce had been revered as a place where earth and water spirits converged.

The town quickly became a thriving tobacco port, with ships sailing up from the Chesapeake Bay to load Virginia's most valuable export. The same river that had carried Indigenous canoes to ceremonial gatherings now carried European vessels laden with plantation crops cultivated by enslaved labor.

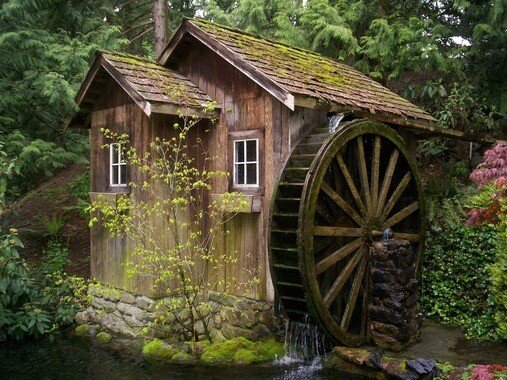

1720: Thornton's Mill

Major Francis Thornton II builds his grist mill at the falls (~1720), becoming the first major industrial use of the sacred landscape. His appropriation of the Indian Punch Bowl symbolizes the colonial transformation of sacred space into private property. The mill utilized the same powerful waters that had drawn Indigenous ceremonies for millennia, marking the beginning of systematic exploitation of the fall line's natural power.

1728: Fredericksburg Founded

The town was established at the fall line to take advantage of water power and river transportation. Significantly, this is the same year the Manahoac are last noted in records as a distinct people. Colonial planners saw strategic and economic value where Indigenous peoples had seen spiritual significance.

1730-1770: Colonial Development

The town grows as a tobacco port and commercial center. Mills multiply along the fall line, harnessing the same powerful waters that had drawn Indigenous ceremonies for millennia. By the Revolutionary War era, Fredericksburg had become a significant commercial center.

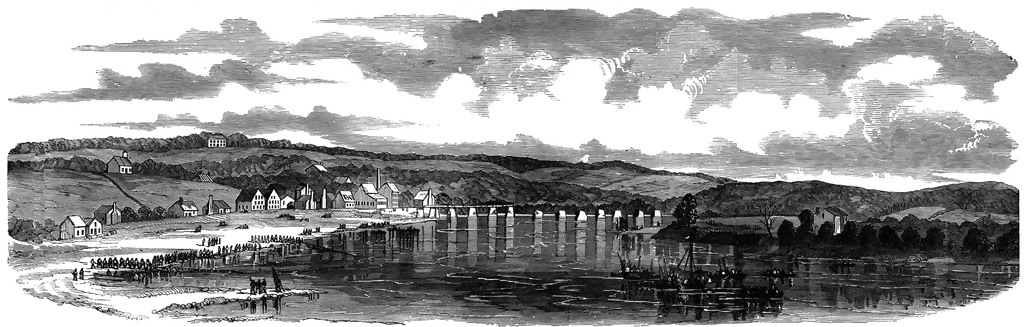

1798: Dunbar's Bridge

Robert Dunbar constructs the first bridge spanning the Rappahannock at the fall line, ending nearly 70 years of ferry service. The bridge required an annual payment to the Thornton family of £500 "forever after" - an enormous sum that remained in force for nearly a century. The bridge symbolized the complete transformation of the sacred crossing into commercial infrastructure.

1808-1826: Bridge Struggles

Dunbar's bridge washes out twice during major floods, demonstrating the continued power of the river that Indigenous peoples had revered. Each time, Dunbar rebuilt at his own expense, testament to the bridge's commercial importance.

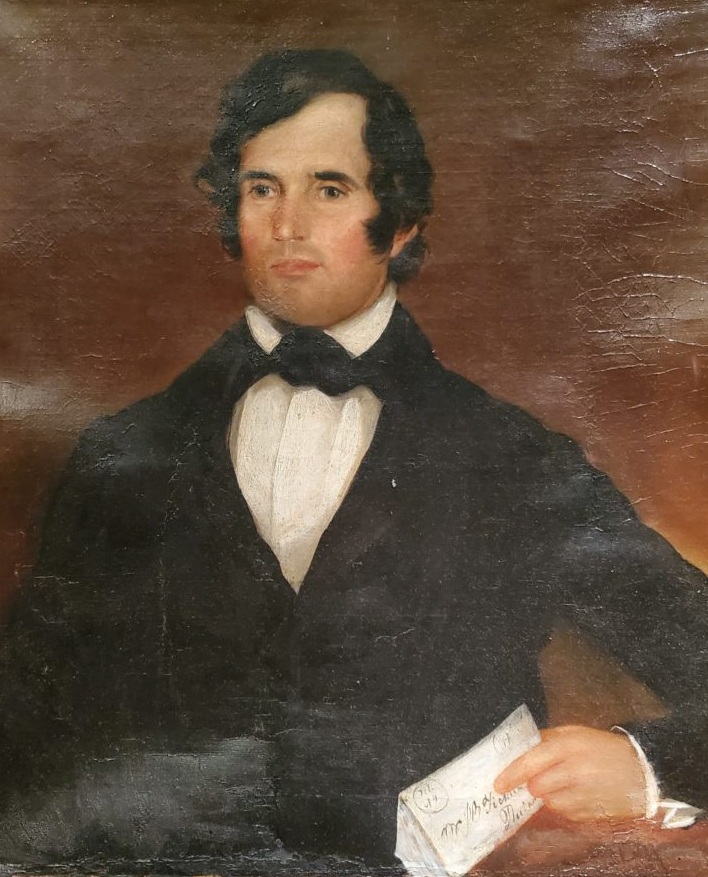

1847: Ficklen's Acquisition

Joseph B. Ficklen purchases the Falmouth bridge from Dunbar's heirs, inheriting both the toll revenues and the massive Thornton annuity. The Ficklen family's ownership of the bridge, mills, and Belmont estate made them one of the most powerful families controlling the fall line's transformation from sacred landscape to industrial complex.

🏭 Modern History

Industrial Age to Present Day

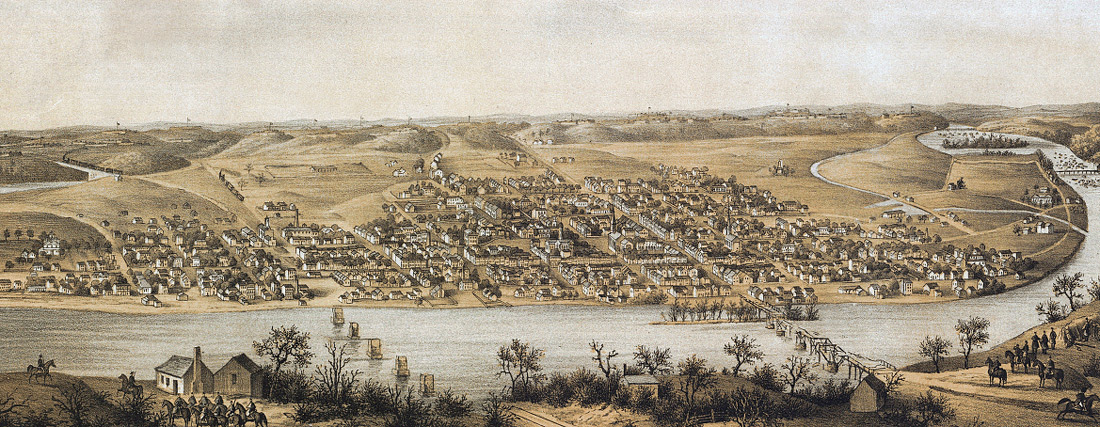

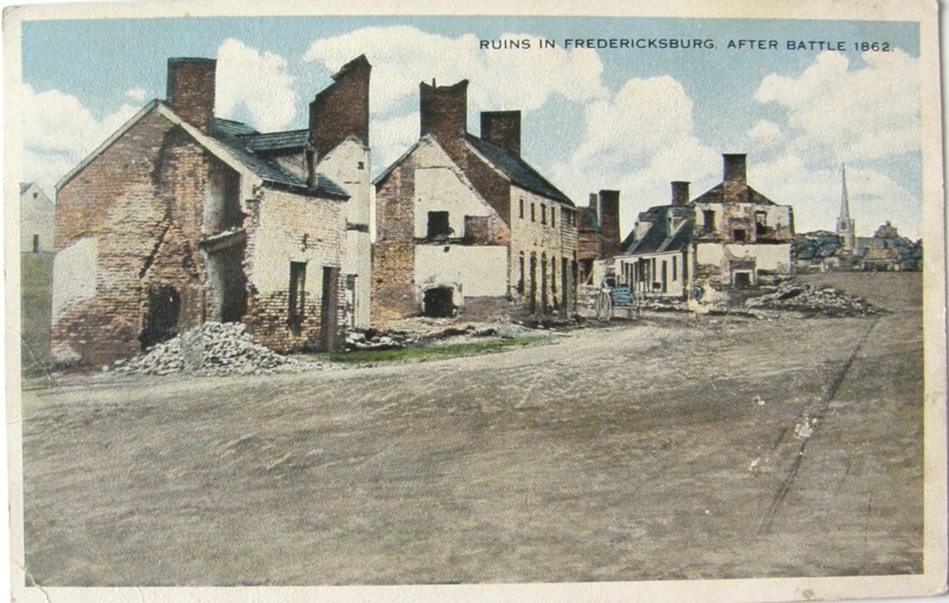

1862: Civil War Era

The fall line becomes a strategic military position during the Civil War, with both Union and Confederate forces recognizing the importance of controlling the river crossing and industrial infrastructure. The Battle of Fredericksburg transforms the sacred landscape into a battlefield.

1887: Electric Power

The Rappahannock Electric Light and Power Company is founded, harnessing waterpower for electricity generation. On November 3, 1887, Fredericksburg is illuminated by electric lights for the first time. The same rapids that had been understood as the dwelling place of the Great Serpent now powered the modern industrial age.

1901: Expanded Hydroelectric

A new hydroelectric plant is constructed on the lower raceway near the Falmouth Bridge. The systematic harnessing of the fall line's power reaches its peak, with multiple mills, bridges, and power plants transforming the once-sacred landscape into Virginia's most industrialized river corridor.

20th Century: Urban Development

Continued urban growth and development further transforms the fall line landscape, though some sacred sites remain visible and accessible. The recognition of Indigenous heritage begins to emerge in archaeological research and cultural preservation efforts.

1912-1946: Walter Plecker's "Paper Genocide"

Walter Plecker, head of vital statistics in Virginia, implements what amounted to "paper genocide" against all Virginia Indians. A follower of the eugenics movement and white supremacist, Plecker denies the existence of Virginia Indians, claiming there were no "true" Indians in Virginia. He enforces a racial classification system recognizing only "white" and "colored," forcing Indigenous peoples to disappear from official records.

1924: The Racial Integrity Act

Virginia passes the Racial Integrity Act, making interracial marriage illegal and officially recognizing only two racial classifications: "white" and "colored." Plecker uses this law to systematically erase Indigenous identity from official documents. Many Virginia Indians are forced to leave the state to escape this aggressive campaign. Ironically, this same year the Indian Citizenship Act grants all American Indians United States citizenship.

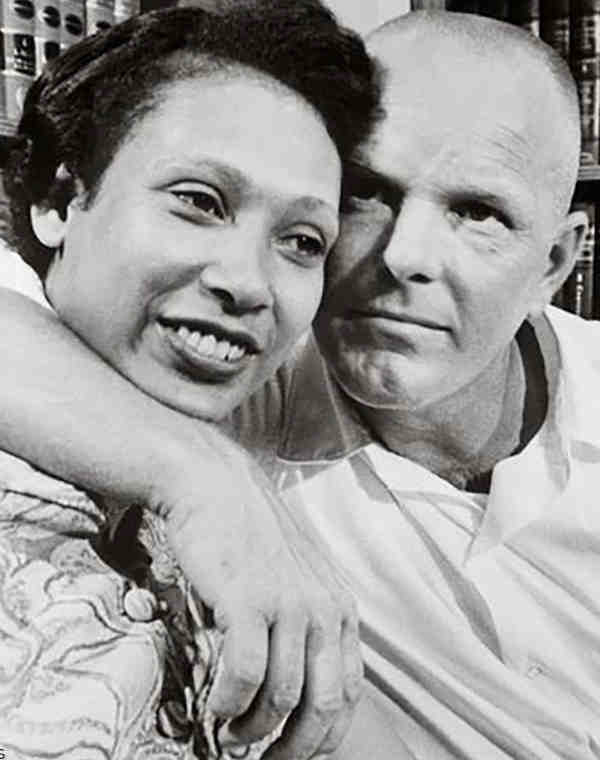

1967: Loving vs. Virginia

The United States Supreme Court overturns the Racial Integrity Act in Loving vs. Virginia, declaring: "Under our Constitution, the freedom to marry, or not marry, a person of another race resides with the individual and cannot be infringed by the State." Virginia Indians can now marry freely and, more importantly, change their birth certificates to accurately reflect their Indigenous identity (for a fee until 1997).

1980s: Virginia State Recognition

By the end of the 1980s, seven tribes receive recognition by the Commonwealth of Virginia. Six are part of or allied with the historic Powhatan Chiefdom: the Pamunkey, Mattaponi (both maintaining their reservation lands from the 1600s), Upper Mattaponi, Chickahominy, Eastern Chickahominy, Nansemond, and Rappahannock. The Monacan Nation, never part of the Powhatan Chiefdom, also gains state recognition.

1990s-2009: Federal Recognition Efforts

Six state-recognized tribes (excluding the two reservation tribes) begin seeking federal recognition through the Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act. After multiple attempts, the bill reaches its farthest point in 2009, passing the House and reaching the Senate Legislative Calendar on December 23. However, Senator Tom Coburn (R-Okla.) places a hold that prevents a Senate vote, and the bill dies at the end of the Congressional session.

2010: Expanded State Recognition

Three additional tribes gain recognition by the Commonwealth of Virginia: the Patawomeck, Nottoway, and Cheroenhaka (Nottoway). This brings the total to eleven state-recognized tribes with approximately 5,792 total tribal members. Collectively, these tribes own less than 2,000 acres of land. The Mattaponi and Pamunkey continue their yearly tribute payments of fish and game to the Virginia governor, as required by the 1646 and 1677 treaties.

2011: Renewed Federal Recognition Push

All six tribes restart the federal recognition process, introducing bills simultaneously in both the House (H.R.783) and Senate (S.379). The Senate Committee on Indian Affairs approves the Senate bill on July 28, 2011, while the House bill remains in subcommittee. Both bills face the same deadline pressure: passage by the end of 2012 or starting the entire process over again.

21st Century: Recognition and Preservation

Growing awareness of the sacred significance of the fall line leads to efforts to recognize and preserve Indigenous heritage sites. The Sacred River Corridor Theory emerges as a framework for understanding the spiritual geography that underlies modern Fredericksburg. Despite centuries of suppression, Virginia's Indigenous peoples continue their fight for recognition and the preservation of their sacred landscapes.

Surviving Traces of the Sacred

It is important to mention that the colonial era overlays didn't erase all traces of native presence. Major Thornton's mill (built ~1720) and later milling infrastructure certainly disturbed some areas, but large stretches remained undeveloped until much later.

Even into the 1800s, local historians were aware of the "Indian Punch Bowl" and sometimes found "arrowheads and Indian graves" on area farms. One such account from the 19th century mentions an "Indian burial" found not far from Fall Hill, though details are scant.

If any burial or ossuary existed at the falls, it might have been on higher ground (to avoid floods) – possibly on the bluffs now topped by residential neighborhoods. Without modern archaeological surveys, these remain speculative. However, given the pattern noted by archaeologist Julia King (ossuaries in view of settlements), one might expect an ossuary on a prominent knoll within line of sight of Ficklen Island.

Future investigations (with cooperation of descendant tribes and property owners) could look for subtle soil discolorations or phosphate anomalies that indicate former bone deposits, as has been done along other Virginia rivers.

Ficklen Island Legacy: The island that bears Joseph B. Ficklen's name became central to the industrial transformation of the fall line. Beyond his bridge ownership, Ficklen operated major mills and controlled much of the river's commercial traffic. His family's development of the island's resources represented the final transformation of Indigenous sacred space into private industrial property. The island's strategic position - the same qualities that made it ideal for ceremonial gatherings - made it perfect for controlling river commerce and waterpower.